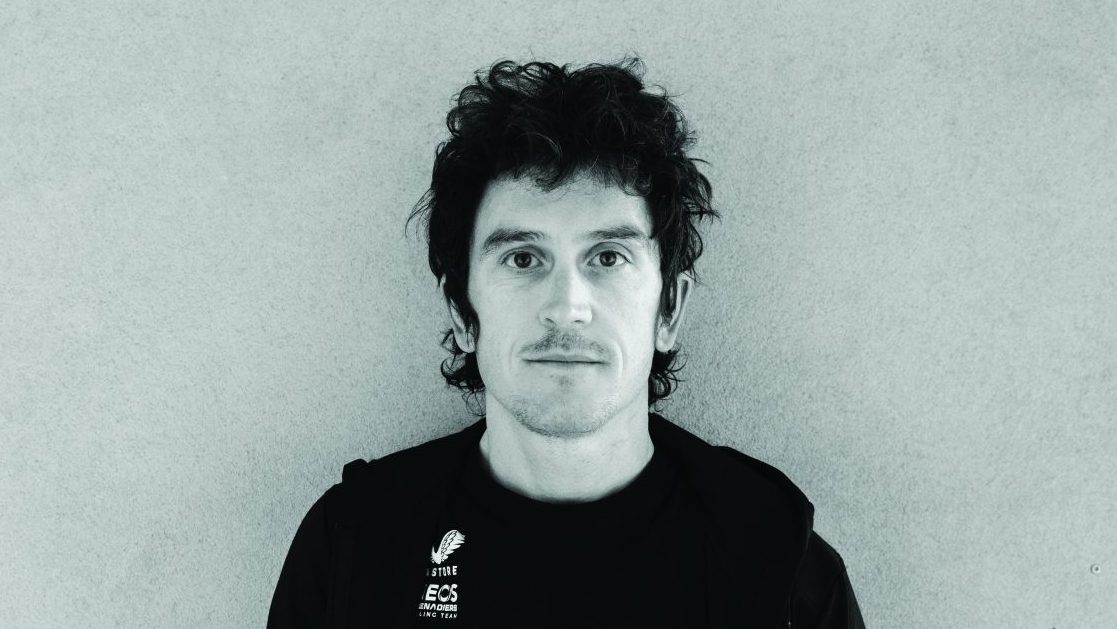

Just what goes into beating a world record? Cyclist follows endurance specialist James MacDonald as he attempts to break the 100-mile indoor record

Words James Spender Photography Mike Massaro

At 2:05pm on 21 February 2024, James MacDonald let go of the spectators’ fence and rolled down the banking towards the racing line.

With gravity on his side to help spin up his huge 62×17 gear, the 53-year-old Scot made the first pedal rotations towards his target: ride 100 miles around London’s Lee Valley Velodrome in less than 3 hours 46 minutes and 16 seconds.

Train. Pedal around in a circle 644 times. Time it. Become world record holder. Simple. Only it isn’t.

There’s a whole lot more that goes into a world record attempt, as we found out when we caught up with MacDonald after his latest endeavour.

And it doesn’t always go to plan.

Proven ability

An experienced ultra-cyclist, MacDonald currently holds the world records for the fastest return from Land’s End to John O’Groats – a traversal of the length of the island of Great Britain, from south to north – at 2,776km in 5 days 18 hours and 3 minutes, set in 2017.

He also holds the fastest 100km cycled on an indoor velodrome – 2h 19min 19sec, set in 2021.

Over the years MacDonald has taken on myriad other records, some successful then overthrown, others close but no cigar.

Which begs the question, how does a rider in the business of breaking records choose which scalps to go for? The answer lies in the process itself.

‘I took on the 24-hour record last May, and I broke a couple of age-group records within that – the fastest 500km and fastest 300 miles [13:52:13 and 13:24:19 respectively] but I didn’t break the 24 hour,’ says MacDonald.

‘It was just brutal, but pretty quickly afterwards my race engineer, Toby [Ellis] said, “Right, we’re going to come back and do the 100-mile record.

It’s 100km pace but a little bit less, so you just need to ride at 100km pace, and then just do another 60km.”

So it was because of the disappointment of the 24 that I wanted to do the 100-mile. I know my FTP, I know the power needed, I know it’s doable.’

In a sense this is how all modern speed records are undertaken on the track (road is different, for example the 100-mile outdoor record is officially held by Christoph Strasser at 3:32:58, with an unofficial record claimed by Jonathan Parker at 2:50:12 with a 33.6kmh tailwind).

Riders have a huge amount of data at their disposal, and given the indoor track is a controlled environment, ‘all’ a rider needs to do is ascertain they can produce the effort needed to keep to a record-breaking pace, then ride at that pace.

‘For me, 67kg with the drag coefficient I have, we worked out I needed to ride at 273W to beat the record,’ says MacDonald.

With his FTP of roughly 320W, this was perfectly achievable. Still, further metrics and clever choices could all help.

Rules and data

Ultra-distance records are different kettles of fish to things such as the Hour record, but less because of the distances as because of the rules.

‘Pretty much anything longer than the Hour isn’t governed by the UCI but by WUCA, the World Ultra Cycling Association,’ says MacDonald.

‘They validate it, and if it’s a world record [as opposed to an age-group record], they pass it to Guinness World Records.

‘In terms of the rules, the bike has to be a “standard” bike, which really means anything that isn’t a recumbent.

The WUCA rules also permit a race radio and a head unit.’ This differs to the UCI rules, where radio contact is banned and various metrics can be measured but the rider must not be able to see the live data, hence head units get taped under saddles.

Similarly, where a UCI-compliant bike must adhere to strict guidelines such as handlebar setup and saddle tilt, a WUCA bike could allow a rider to ride in the ‘praying mantis’ or ‘superman’ positions used by Graeme Obree and Chris Boardman in the 1990s indoor record and promptly banned by the UCI for presenting ‘an unfair advantage’.

It’s interesting, then, that MacDonald eschews such gains, even if they are legal.

‘I want the bike to look as normal as possible, so if I break a record I’m not in the position where someone says I only did it because of my kit. I want it to be pure.’

But ‘pure’ is context-dependent, which is why MacDonald sought to optimise his kit and riding position in the wind-tunnel with help from aerodynamicist Simon Smart of Drag2Zero and kit sponsor Endura.

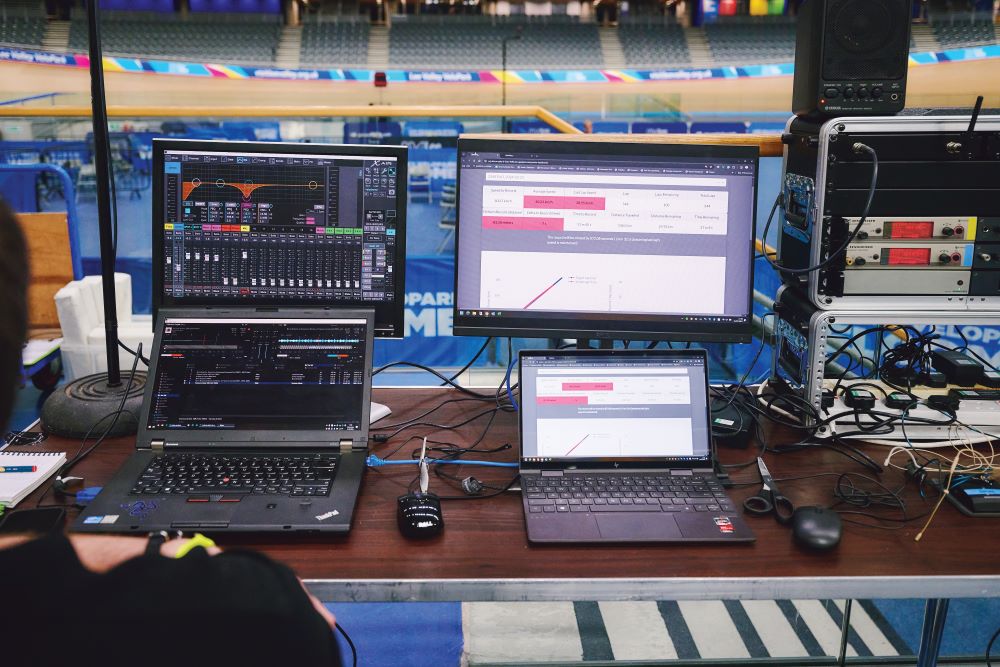

One area that MacDonald does seek to mine for all it’s worth, though, is data, and crucial to that is radio contact and a head unit: ‘I have three fields on my head unit: speed, power and heart rate.

I know the power I need and I know the heart rate zone I need to sit in to be able to sustain it.

I have Toby on the radio and he’s in contact with my nutritionist who’s looking at my glucose levels, which are measured by a continuous glucose monitor on my arm and analysed through the Supersapiens app.’

MacDonald explains a glucose level of 120mg/dL would be about right for a ride where you can ‘still chat to your friends’, but for the 100-mile record, around 160mg/ dL is more likely.

The key, though, is consistency: ‘You want to avoid peaks and troughs, because when glucose goes high to low on the track you can feel like you’ve bonked.’

Such monitoring allows MacDonald’s nutritionist to fine-tune his fuelling so it’s easier to control heart rate and produce sustainable power. So did it all work on the day?

The reckoning

‘I did the warm-up thinking, “I don’t feel good,” and got on the track and felt like shit,’ says MacDonald.

‘My legs felt sore straight away and my stomach was a bit funny.

Power was fine, heart rate was fine, glucose fine. But it didn’t feel good.

I fed that back to the team over the radio, but when it’s how you feel, there’s nothing they can do.

‘I was on pace for the first hour and a half but the discomfort felt like I was riding the last hour and a half.

At first the pace was hard, then awkward, then just not possible.

I ended up being on schedule to set a time of around four hours, so massively off the 3:46.’

Looking back now, MacDonald realises he had a stomach bug, which in the end took him weeks to get over, but even then – testament to his team’s support and his conditioning – he was on course for the British 100-mile record.

Only here too he hit an insurmountable wall.

‘We had the track booked until 6pm, and although I could have kept riding and ridden 100 miles in under four hours, and although the only reason for struggling on like that was to set the British record, I was told to stop by the velodrome,’ he says.

In the end MacDonald says he was only able to ride around 90 miles, the velodrome officials calling time to clear the track for other paying users, despite protestations from MacDonald’s team.

Frustrating, you’d think, but in true steely form – the kind that ultra-distance record breakers need – MacDonald remains good-humoured and stoic about it all.

‘To be told when I’m nearly finished that I couldn’t even do that was pretty disappointing, although to be fair at the time I couldn’t have cared less because all I wanted to do was stop.’ It’s not the end, though. It never is.

MacDonald says he’s coming back for this record later this year, albeit perhaps at another venue, and this time, hopefully, without a stomach bug.

How to beat the world

The bike, kit, training and nutrition for a 100-mile world record attempt

THE KIT

For his fastest 100-mile indoor record attempt, James MacDonald rode a BMC Trackmachine TR01 with Mavic Comète disc wheels fitted with CeramicSpeed bearings and Vittoria Pista Oro tubular tyres, 19mm run at 190psi (‘which was like riding concrete’, says MacDonald).

Other components included Drag2Zero aero bars; Rotor 2InPower track chainset (160mm); CeramicSpeed bottom bracket; 17t Digirit carbon sprocket and 62t carbon chainring.

MacDonald wore a custom Endura skinsuit with silicone surface treatment to reduce drag further, and an Endura Drag2Zero aero helmet with custom 3D printed tail designed specifically for his riding position.

TRAINING

A typical training week saw around 15 hours of riding plus gym and physio time, all fitted around MacDonald’s day job working for Google: Monday rest, with 1h physio; Tue pm 90min interval session (turbo); Wed am 60min gym session, pm 90min interval session (turbo); Thurs pm 90min interval session (turbo); Fri pm 2h interval session (turbo or road); Sat am 60min gym session, 4h ride (road); Sun 4-5h ride (off-road).

NUTRITION

At 8am on the morning of the attempt, MacDonald took a probiotic tablet, vitamin tablet, 500ml electrolyte mix, 5g creatine in water.

At 8:30am he ate four poached eggs with two yolks removed, a brioche bun and drank a cup of coffee. At 10:30am he drank 500ml water.

At 12pm 500ml electrolyte drink mix. At 12:15pm 60g porridge, one banana, maple syrup and ginger tea.

At 1pm a banana and oat milk smoothie. At 2pm an energy gel on the startline. At 2:05pm he set off.

During the record attempt, MacDonald drank a maltodextrin energy mix, 400ml per hour plus one energy gel, designed to deliver a blood glucose value of around 140-180mg/dL.