Before gravel there was the ‘Jobst ride’. During the 1970s in America, Jobst Brandt led the way in taking bikes where they weren’t supposed to go, and inspired a generation of adventurers and framebuilders. This is his story

Words MAX LEONARD

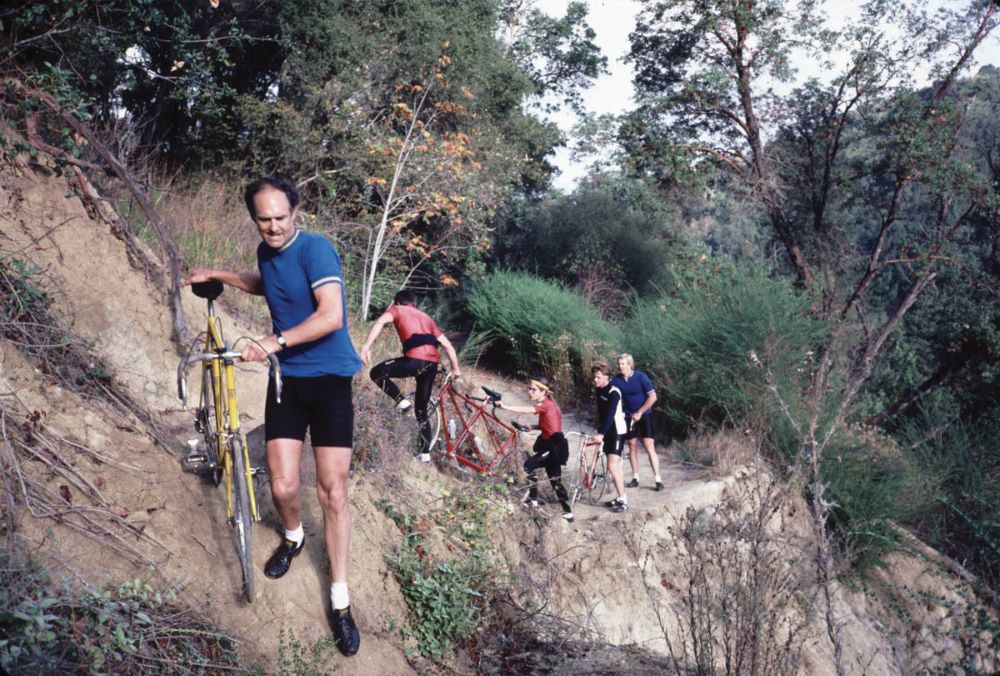

California. The Santa Cruz Mountains, south of San Francisco. A logging track through the majestic redwoods.

It’s a quiet Sunday morning in the mid-1970s.Suddenly the peace is broken by the sound of tyres in the dirt and four… six… eight cyclists burst onto the scene, chasing a giant charging up the hill on a red road bike the size of a barn door.

As quickly as they arrive, shouting and breathing hard, they are gone.

Minutes later, a final cyclist trudges into view, bike slung over his shoulder.

Its buckled, punctured front wheel is jammed against the fork. It’s going to be a long way home.

Welcome to the ‘Jobst ride’. The man being chased is Jobst Brandt – opinionated, sometimes obnoxious, often inspiring. A 6ft 5in powerhouse who broke Campagnolo cranks and axles for fun as he took his steel Cinelli Supercorsa frame to places entirely unsuitable for the skinny tyres and racing geometry of a classic road bike.

On Jobst rides you went where Brandt decided. You stopped when he stopped, drank when he drank (he didn’t carry bidons and drank only from streams).

You would take on dirt roads, forest tracks, landslides, and then eight or nine hours later you dropped back into town, completely exhausted, covered in mud, but happy.

Among the initiated, Jobst rides were infamous. Forget gravel bikes – these were mountain bike rides before mountain bikes had even been dreamed up.

And the riders were among the state’s best racers, which meant the country’s best. Names like Tom Ritchey, Gary Fisher and Eric Heiden.

The Bay Area at this time was a place where small seeds grew into large trees. Brandt, his rides and his friends had an outsized influence on cycling.

So who was he?

A life on two wheels

Jobst Brandt was born in 1935 and grew up in Palo Alto, California.

Now at the heart of Silicon Valley, home to global titans such as Apple, Google, Facebook and Tesla, it was then a sleepy ranch town surrounded by orchards and bordered by Stanford University.

He was the son of a German professor who had escaped the Nazis and fled to the US in the 1930s.

Post-war, the family spent a year in Switzerland and took weekend car trips into the Alps, which later became very significant to Brandt.

As a teenager, he liked dirt and he liked speed. Both were within easy reach in the Santa Cruz Mountains between Palo Alto and the coast.

His first two-wheeled love was motorbikes. A mechanical wizard, he built a Vincent motorbike out of a pile of parts in a box, without instructions.

Then he rode it around the mountains until the local police, stopping him for the hundredth time, threatened to take away his licence if they caught him again. That’s when he switched to pedal bikes.

Brandt joined a club called Pedale Alpini and competed in local road races a few times, turning up at first on a three-speed with a straight handlebar he’d lifted from a Vincent.

But he soon worked out racing wasn’t for him. Road racing was sneaky and tactical, whereas in Brandt’s purist ideal, the strongest rider should win.

So he went back to his long, long rides in the mountains, sometimes heading on multi-day trips with friends, sleeping rough or in railway workers’ bunkhouses, to the high, high roads of the Sierra Nevada (Tioga Pass tops out at 3,031m).

After graduating in engineering from Stanford, he shipped to Germany with the US Army Corps of Engineers.

In the summer of 1959 he went on his first cycling tour of the Alps, dropping in on Cino Cinelli in Milan to give the maestro some of his thoughts on framebuilding.

‘I asked Mr Cinelli what the greatest road in the Alps was,’ wrote Brandt in his ride report.

‘To which he replied without hesitation, the Stelvio, but that I might not like it because it was unpaved. That especially caught my interest.’

And this was Brandt’s agenda for the next half century: engineering, cycling, Alps, repeat.

All documented in amazing photos and ride reports.

Dishing the dirt

In 1964, after four years working at Porsche, Brandt returned with his young family to Palo Alto and slotted back into his old cycling life. By the mid-1970s, the Jobst ride was becoming an institution.

Meet at Brandt’s house at 8am on a Sunday. Rolling by 8:30. Back before dark. Possibly.

The rides were fast and brutal; Brandt had an engine that even state champions found hard to match.

‘No one rode dirt to the extent that Jobst did,’ Tom Ritchey says of those years. ‘There were people that would ride, you know, little efforts, like John Finley Scott.

And of course the Marin guys talked about doing it, but they were mostly going downhill and bombing around.

There was no one that was putting the miles in.’ But the rides were also great discourses on nature, history and engineering.

Brandt took teenagers Ritchey and Peter Johnson (who would also become a master framebuilder) and drummed into them everything he knew about materials and engineering principles.

And the boneshaking dirt roads were a natural product testing ground for the frames and components the young Ritchey was already making.

He clearly recalls Brandt’s warning: ‘Ritchey, you better be careful about building too light, or changing standards; those things have been around for a hundred years for good reason.’ Gary Fisher, the mountain bike innovator, was also a Jobst ride alumnus: ‘Jobst was always talking about how stuff is made and why it’s made that way, why it makes sense for a bicycle.

He talked about materials, design, how it was done, and it was great to know, but the big thing I learned was the practical thing, the act of riding a bike.’

A couple of hours’ drive north from Palo Alto, across the Golden Gate Bridge, the legendary Repack races were happening – early downhill races so fast riders needed to ‘repack’ their overheated hubs with grease. Charlie Kelly, Joe Breeze, Fisher and others were inventing a new sport and a whole new machine.

But when asked by Fisher and Kelly to build frames for their fledgling company, MountainBikes, Ritchey took inspiration more from Brandt than from downhill racing.

‘The bottom line was that I didn’t know how interesting this new sort of bike was to me, because when I started it weighed twice as much as anything I would have ever wanted to be involved with,’ Ritchey says.

‘The only way to crack this nut and make it something that was interesting to ride was to make it a true cross-country bike, à la Jobst rides: to have the ruggedness, the durability, with no flat tyres.

All these Jobst-influence factors were built into me and well established.’ So not only was he the godfather of gravel, Brandt influenced the course of early mountain biking too.

Ironically, later on, Brandt gave every sign of hating mountain bikes, but that wasn’t always the case.

Breeze recalls bumping into Brandt in 1977 or 1978 with his original Breezer mountain bike.

‘I knew Jobst from road races, and so we’re talking and he saw it. He admired that frame and what we were doing.

It wasn’t what he was doing with skinny tyres, but at that time he still somehow saw some kinship, even if it had fat tyres.

And maybe it helped that he knew I was a road racer, so I was OK.’ What mountain bikes did, though, was make life more difficult for Brandt.

They opened up his (not-so-legal) deserted trails to more riders, which meant trails began to get shut down.

‘For Jobst, the rise of the mountain bike was the decline of his personal secret forest rides,’ Ritchey says.

Avocet and beyond

It was in the 1970s that Brandt became good friends with brothers Bud and Neal Hoffacker, who ran his local bike shop, Palo Alto Bikes.

They were importing Italian parts and running the first mail-order catalogue for high-end bike bits in the US. Brandt’s photos from his Alps trips appeared on the cover, inspiring people to ride – and buy components – across the US.

When the Hoffackers’ manufacturing ambitions grew, Brandt suggested the brand name Avocet, after the local bird, and even designed them a logo.

Although he was employed full time at Hewlett-Packard, he would drop in after work and spend hours discussing products and critiquing their ideas.

Brandt moonlighted on the game-changing Avocet plastic saddle, and designed the first-ever touring shoe, which appealed to the exploding market for bike touring.

It had a reinforced heel strap, which he patented. Perhaps his first big idea, though, was the treadless tyre.

Nobody made these for road bikes – they were strictly the preserve of track riders. Bud Hoffacker recalls, ‘I said, “I can’t do that. We can’t sell it, Jobst.”

There weren’t any smooth tyres on the market at that point.’ But Brandt convinced him: smooth bike tyres wouldn’t aquaplane in the wet, and more contact meant more traction.

There’s a great Avocet advertisement with a photo of Brandt descending Haskins Hill outside Palo Alto, cornering on his huge frame at a ridiculous lean.

‘We put a gyroscope on the back of the bike so we could record the angle,’ says Hoffacker.

‘A lot of riders didn’t want to keep on going over to see how far they could lean, so Jobst decided he had to be the one to go out and do it. He said, “No one else can do this.”

The inclinometer recorded that he reached 43°. Later, Avocet built a tyre-testing machine, a huge asphalt-covered rolling drum on which the (riderless) lean angle could be precisely calculated.

Avocet’s smooth tyres slid out at 44.5° – considerably better than any of the competition.

Brandt had come within a degree or two of wiping out. The tyres were bestsellers.

But Brandt’s biggest impact came with the Cyclometer, the world’s first handlebarmounted bike computer.

Drawing on his contacts in Silicon Valley, he became obsessed with shrinking the electronics down to a suitable size, with a look and feel that would be just right for a cyclist at speed.

The Cyclometer suffered delays and teething problems, but it had a formidable asset: Greg LeMond.

As a junior, the young Nevadan had raced for the Palo Alto Bicycles team, regularly blowing away the competition, and the brothers had encouraged him to go to Europe and turn pro.

LeMond featured in several Cyclometer advertisements in the 1980s. ‘When I’m racing, I only want three facts… fast. I want speed, distance and elapsed time,’ he states in one.

‘That’s it. The Avocet Cyclometer is perfect. It tells me exactly what I need to know… fast.’ Another boasted that the Cyclometer was used by 82 per cent of pros in the 1989 Tour de France, with a picture to prove it.

‘We sponsored a number of riders, but I would say just about all the riders paid us,’ Bud Hoffacker recalls.

‘They just had to have it because they thought it was part of the secret of why Greg won the Tour.’

An altimeter followed, with Brandt-patented circuits that stopped it – unlike competitors’ models – hugely overestimating the cumulative altitude gained.

All the years Brandt was collaborating with Avocet, the company paid for his annual riding holiday in the Alps – three weeks, 3,200km of product testing – and Brandt would drag a friend over his favourite roads and tracks.

‘To him, riding in the Alps was narcotics. He just loved it,’ said framebuilder Peter Johnson, who accompanied him six times.

‘I think he would do it all day. The only reason we stopped was because it got dark, and in fact that didn’t always work.’

With Avocet, Brandt also published The Bicycle Wheel in 1981. Wheels were his lifelong fascination, but he thought wheelbuilding had always been misunderstood, so he wrote a Stanford-level explanation of the physics of the tensioned wire wheel, as well as a practical guide to building good ones.

‘I don’t believe in shrouding a technically simple process in mystique,’ he wrote. The book became the definitive text, and was reprinted until 2013.

Signing off

In the late 1990s, as befits a Silicon Valley native, Brandt took to the internet.

His reputation spread on Usenet groups and forums as a technical expert – or blowhard, depending on whose opinion you listened to.

He was progressive and innovative, but also stubborn and intransigent: he knew what he liked, and he liked what he knew.

The early years of the internet were a Wild West of no netiquette and frequent ‘flamings’, and, looking back at the exchanges, Brandt’s conduct doesn’t seem much different from anyone else’s.

What must have been insufferable to his opponents was that on engineering topics he was usually right – and he knew it.

Brandt often signed off his emails with: ‘Ride Bike!’ In 2011, he suffered a fall on his bike and did not ride again.

He died in 2015, aged 80. As late as 2008, though, he was still touring in the Alps, pushing his traditional steel frame with its bulky Carradice bag up rocky trails.

Only a few years later, a new generation of riders – who mostly knew nothing about Brandt – would begin dreaming of doing exactly the same.

Jobst on…

…road bikes vs mountain bikes

‘You can do a lot more with a thin and smooth-tyred bike than the MTB crowd believe.’

…the bike industry

‘The bicycle industry is not very high-tech in that most of it is marketing.

The technical innovations are few and are made on a thin margin of expense on the product line.

You see all sorts of ill-designed products annually at the international bicycle trade shows that can be recognised as failures by competent engineers, of which few are employed by the industry, mainly because they cost too much.’

…the Stelvio

‘The Stelvio may not be the hardest, longest, or anything else, but it has a special place in my heart for its magnificent and exquisitely orchestrated landscape.

It seems to have its own Wagnerian accompaniment, magnificent and grand. I’ve ridden it in every weather and it is always an emotional moment at the top.’

Max Leonard is the writer and publisher of Jobst Brandt Ride Bike! out now from Isola Press