In the Dolomites of northern Italy, our route via the Passo delle Erbe and Passo Gardena serves up rugged beauty unlike anywhere else in the world.

Words James Spender Photography Mike Massaro

In Australia, you’d count yourself lucky to find a servo with a stocked pie warmer and a $1 coffee machine. The average service station in Italy, on the other hand, is a culinary delight. Espresso is deliciously rich, arancini are made on-site and there are little tables to stand around and read the paper. People stop there for the food itself, not as an add-on to the petrol.

I can recommend stopping at any of the dozens of such service stations en route from Marco Polo Airport in Venice to the Dolomites in the north of Italy. I can also recommend taking the route that passes through the town of Agordo – so picturesque it might be walled with giant postcards, and a superb spot to grab another coffee. That should give you enough of a boost to continue motoring on to the mountain town of Arabba.

A bit like Italy’s version of Saint-Jean-de-Maurienne – a brilliant base in the French Alps from which to tackle the Croix de Fer, Madeleine and Galibier among others – Arabba sits in a nook of the Dolomites that’s spoilt for choice when it comes to riding options. There are three main roads in and out of town; one is the Passo Campolongo and another is the Passo Pordoi. Further neighbours include the Passos Giau, Fedaia and Sella. There is also a gondola that serves the Dolomites’ most lauded ski system, presided over by its tallest peak and namesake, the 3,343m Marmolada.

I ponder this over breakfast, which I am sad to see is now orchestrated from a kind of pandemic Perspex pulpit. Inside sits the fare, conducted by a dickie-bowed waiter and his tongs. This lends both ceremony and judgement, as my cereal bowl is delivered with aplomb, but an arched eyebrow is cast when I attempt a second round of cake. Gone is the classic breakfast buffet. Gone is gluttonous anonymity. I can no longer eat several breakfast courses and squirrel away a few treats for later. Sadly, this surely is the end of appropriating breakfast goods for picnic lunches.

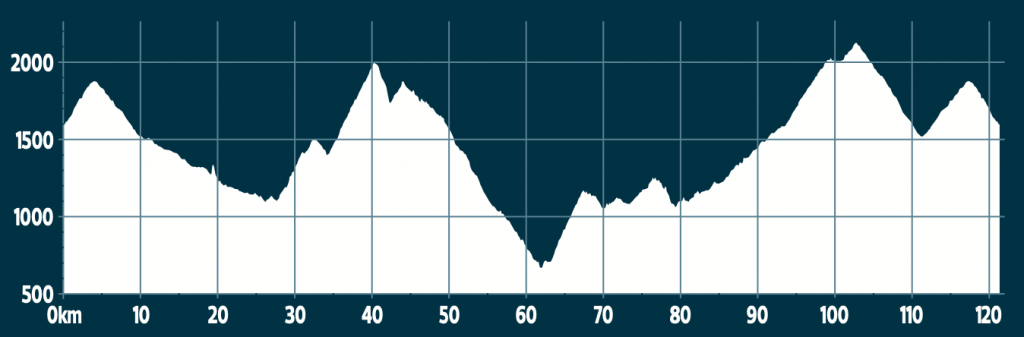

I meet Matthias in the hotel bar, sipping from a tiny cup and dressed, I’m pleased to see, in the same clothes as me – that is, regular kit plus warmers. I’m not sure if it’s me getting older or global warming, but I find it increasingly difficult to decide what best to wear on anything but the hottest days. Especially when a ride starts at 1,600m, will spiral to 2,200m and my weather app says will be bathed in full sun despite the spire of the local church currently prodding through mist.

Road less ridden

Tree branches hang like damp clothes as we roll round Arabba’s only roundabout, heading left and up behind a cluster of bars and shops. Within moments a familiar sting traces across my quads. We are leaving the town

on the Passo Campolongo road, and it goes up.

I tried to ride as much as possible over the summer, but my local routes barely muster 350m ascent over 70km, whereas today is nearly twice that distance and 10 times the elevation. I’m badly prepared, but it need not matter: Italy has brought her A-game to distract me.

Sunburnt larch houses cascading with petunias dot a hillside whose grass would be fit for international bowls. Red and yellow cranes dangle over hotels being refitted for the winter ski onslaught. The road is grey, stained black with condensation. Rhythmic wittering from the trees accompanies the corrugated ticking of our drivetrains. I have missed this so much.

The high point of the Campolongo comes quickly, our climb from Arabba being the 4km ‘easy’ ascent. The angle of the road subtly changes and gravity proffers a hand, so soon our legs are spinning purely to keep loosened. This is a fairly arterial road, and while our speed is decent we do find ourselves being overtaken by the occasional procession of motorcyclists, engines reverberating off the ragged cliffs long before they arrive and for a similar time after they’ve gone.

Matthias explains that this area of the Dolomites is becoming increasingly popular with German motorists, who flock here in their droves to drain weissbier by night and rip through the mountains by day, safe in the knowledge that the Italian policing system isn’t joined up enough to impinge on their lives back home. In the main, though, it is still early enough in the day that our languid descent through Corvara and onto Piccolino proceeds with us and us alone.

At Piccolino we are faced with a choice. This is the beginning of a major climb, the Passo delle Erbe, and there are two ways up the first section. As is common

in these parts, there is the old road and the new road. We elect to take the old road, which is narrow enough not to have much in the way of markings and is boxed in by trees, but the pay-off is it’s much quieter. Today, in fact, it is wonderfully deserted.

This is a proving ground that Matthias says he takes on periodically to assess his form, and I quickly find out why. The road immediately bucks and rears, hairpins offering little respite and the closeness of the trees suffocating. I want to claw at my armwarmers, which now feel horribly restrictive.

Evidently Matthias is in decent shape and does that thing that all riders in decent shape are wont to do on climbs, and that’s have a conversation. Thus I learn he used to be a local ski champion, at one point the 17th best slalom skier in Europe. It now makes sense as to why his torso is as hewn as his legs. Not your typical scalatore, but every bit a man possessed of a VO2 max of 70. I also learn he did ski jumping too, and that this necessitates the jumper to absorb the equivalent impact upon landing of a 900kg leg press.

On another day I might smell the wild herbs that give this pass its name, but today my olfactory stations have no useful place in my respiratory chain.

The old road joins up with the newer road and with it comes a steadyish stream of two-wheeled traffic. I am particularly taken by the sight of an elderly woman on a very upright mountain bike, cheerful in the extreme despite her obvious labours. A short descent follows, just long enough to collect my thoughts and appreciate the surroundings.

Every mountain range has its personality, and were you to come across Europe’s most famous at a party, it would be the Alps urbanely waving around a cigarette while the Pyrenees showed up late and spiked the punch. The Dolomites, meanwhile, would sit in the corner reading a thumbed copy of Kafka. It is the broody hipster, the most mysterious of the three.

Today that moodiness manifests in the way the peaks are slipping in and out of cloud, as if it is they that are moving, not the skies. There’s a colour to them when the sun hits them just so, a pink-purple phenomenon know locally as enrosadira, but today the Dolomites are looking more serious, if not unfriendly.

Beetle’s about

The sign at the pass’s summit is informative, telling us that not only have we made it, but also that we now sit at 1,987m plus the height of a top tube. Motorcyclists gather in front of the sign for pictures, like conquering heroes. But it’s the sign’s words that are revealing: Ju de Börz, Würzjoch, Passo delle Erbe. Three names for the same place, one German, one Italian and one ‘Ladin’, Matthias explains.

While we are in northern Italy we are also, somewhat confusingly, in South Tyrol, a region once under Austro-Hungarian and Bavarian rule. Thus every place here has its German and Italian names, but also its name in Ladin (that’s the Ju de Börz part), a local language born out of Roman occupation (see box on p108). Ladin exists as a piece of cultural identity as much as anything, with a good parallel perhaps being Welsh.

We do our own cursory photos with the sign and then it’s time for the descent. An arrow-straight road disappears into the regimentally stacked pines, rounds a tight left hairpin then redoubles its efforts at flat-out speed until the next corner. A sign pointing us towards Klausen whizzes by and the grey mountains grow taller as we drop in height. I can feel the air, once wispy and chill, begin to warm.

The washed out hues higher up have become more vibrant and that lawn bowls grass has returned, bringing with it a condensing number of tiled buildings. A sign with its own miniature roof on one hairpin bids ‘Willkommen’, and a few corners later we find ourselves arriving at a piazza that feels more Mediterranean than Dolomite mountain. It’s overlooked by an ornate church, St Peter’s, which explains the village’s name, San Pietro.

We position ourselves outside a cafe in the sun and watch a steady stream of expensive cars gun their engines around the corner of the square. A few other punters, mostly cyclists, look up disinterestedly at this million-euro parade. It’s only when a throaty whine starts growing louder that everybody puts down their espresso cups. A bright yellow convertible Beetle careens around the corner and comes to a put-put-putting stop. There are murmurs of appreciation. The only thing to complete the scene would be for the driver to wave his straw hat.

Chop chop

We pay our respects in the church, our cleats echoing off the tiled floor, before rejoining the road and its ongoing descent. We’re close to civilisation now and it’s later in the day, so traffic of all types is thick. I’m glad when Matthias whistles at me to slow down and make a hard left at a sign for Gudon.

We pass a sawmill in full swing, still dealing with the fallout of storms that turned much of the Dolomites’ thick forest hair into little more than a comb-over. The road is at first strewn with mud and sawdust, before sidling off into overhanging conifers and dropped leaves.

This is the kind of climb you find all over this area. They appear out of nowhere and are narrow, poorly surfaced, short and incredibly steep. It’s a horrible joy, the kind of thing you look for but recoil from once you’ve found it. At just 5km long it’s dispatched soon enough, but our reward comes in the form of a puncture for Matthias, which comprises part annoyance (him), part pocket picnic (me).

Once we’re rolling again Matthias is keen to make up time, so what might otherwise be a gently undulating road with slowly opening views becomes a personal audience with my stem and an ex-skier’s backside. Still, I’m glad of the pull as we roll through Ortisei, the largest conurbation in these parts and, in the nicest possible way, the sort of place that would be great fun at night but is otherwise best described as a ‘gateway’ to its beautiful surrounds. Most specifically, the Passo Gardena.

Hairpins to paradise

It’s always hard to say where a climb starts. Is it the moment the road goes from flat to up? Is it from a specific town? Even a specific junction or road sign? Thus in a sense we have been climbing the Passo Gardena for some time, the road beating a path back up into the mountains since Ortisei. Yet the purist will say the Passo Gardena starts from Selva di Gardena. No wait, it’s from Selva-Wolkenstein. No, hang on, it’s from the outskirts of Plan De Gralba, where the SS242 becomes the SS243. Frankly, it doesn’t matter.

All I need to know about the Passo Gardena happens before my eyes. The first third comprises agreeably coiled hairpins that dither at low gradients, seemingly with no urgent place to go. Then the road levels a touch before rounding to hug its mountain base, and for the first time we’re in shadow, peaks so high and awkwardly angled that it’s impossible to find sky over my right shoulder. But no sooner has the Gardena lulled my legs into a steady beat than it steepens to sweep right, left and right again, then unfurls onto what I assume is the ‘garden’ itself – an incongruously flat, boldly green plateau that looks stolen from the valleys below.

We pause at the top to take it all in, a half dozen landscapes stitched together to form one incredible patchwork. We clip back into our pedals and roll away. There’s one more climb to go, the Passo Campolongo, which we rode this morning only in reverse. But before that is the small matter of the Passo Gardena’s descent. A dozen or so hairpins are laid out below us over 8km of road. Sightlines are excellent, the only traffic is other cyclists. The road is ours.

The route we took

To download this route go to komoot.com/tour/293085450 or scan the QR code. Head north out of Arabba on the SP244/Passo Campolongo, which segues into the SS244 before heading through Corvara. Stick with the SS244 all the way to Piccolino at around kilometre 28, where you’ll see the road double back on itself next to a bus stop. Take that left, ride over the bridge and just before the Agip garage head right onto the old road. At around 33km the old road joins with the SP29/Passo delle Erbe. Continue until San Pietro where a stop for coffee at Hotel Kabis is a good idea. Follow the natural path of the road towards Gudon, paying special attention for a sawmill on your left and a tight left-hander at around 70km, signposted Gudon. Proceed up the climb, ride through Laion, taking the SP139 out of town, through another (but different) San Pietro and follow signs to Ortisei. From here it’s a case of following the main road, SS242, down to Plan de Gralba, then turning left at a sign for SS243/Passo Gardena. Make the ascent, descend to Colfosco, then head for Corvara and retrace the Passo Campolongo back to Arabba.

The rider’s RIDE

Some years back I tested a ‘regular’ Diamante and found it to be stiff with a capital ouch, a quintessential Italian race bike for smooth roads and even smoother legs. It was brilliant, but not for everyone. Fast-forward to 2020 and this latest incarnation holds more universal appeal. It’s a better-behaved bike in a sense, yet still one with a healthy dose of aggressive attitude.

Geometry-wise things stack up to be racy, the bike sporting a short wheelbase, stout rear triangle and front end kept low by Basso’s -11° stem (most bikes are -6°). Stiffness-wise the SV still packs a hefty punch, and DT Swiss 1400 PRC wheels with mid-section aero profiles ensure the bike climbs in a spritely manner and more than holds its own on the flat. But where it has come on leaps and bounds is comfort. The spindly fork legs help offset the stiff bar/stem combo, and there’s an elastomer-damped seatpost. But it’s the wider tyres, here 28mm but with room for up to 32mm, which give the SV its more well-mannered ride. It still comes alive when it matters, though. Point it down something twisty and steep and the Diamante descends like a rollercoaster.

How we did it

Travel

The best time to visit the Dolomites is from March to June or from September to mid-October, when the weather is warm but it’s not the school holidays (the area can get busy during this time). Venice Marco Polo is the closest airport to Arabba, a 2.5-hour drive away.

Accommodation

We stayed in Arabba, a great base for a cycling holiday with many more routes to ride besides this one. The area has a strong German influence so expect great beer, and if you stay at the Hotel Malita (hotelmalita.it), expect some seriously good pasta and a blindingly good tiramisu. See arabba.it for more details.

Thanks

Our warmest thanks to Jessica De Vallier from the Arabba tourist board, who found us the excellent Hotel Malita at the last minute and organised everything down to our post-ride beers (NB it has to be weiss). Thanks also to Matthias Thaler for guiding us around, and Oscar Crepaz for being such a cheerful driver for our photographer, Mike.