Cyclist sets off for a tough but scenic route south of Hobart through the wonderful Huon Valley with ex-Team Novo Nordisk pro Justin Morris as a guide.

Words Imogen Smith Photography Marcus Enno

We meet at Fern Tree tavern, a 1970s bunker of a pub at the crossroads of all the biggest, meanest climbs in and out of Hobart. Here, lumberjack-style locals and their bitzer dogs mix with half-clad trail runners, gaitered, storm-jacketed hikers, and of course, cyclists decked in Lycra. Smoke drifts up its chimney from a huge hearth year-round. It’s never really hot enough at Fern Tree to put out the fire. It’s still the only place I’ve ever ordered tea and hot chips as a meal combo.

Fern Tree Tavern is a fitting place to start and finish any tough ride in the cool Tasmanian weather. Today I’m riding a route that Justin Morris, head coach at Mind Matters Athlete Coaching and former pro cyclist, says is one of the best in Tassie.

Mind and body

Justin has spent the last few days scouting epic routes around Hobart for his next Mind Matters Athlete Training Camp, where he’ll host 14 amateur athletes who are looking to get fit and find challenges in the Tassie hills. Today he has invited me on the ride he’s most excited about: the Huon Valley Loop. It’s the kind of route that promises to challenge the mind as much as it does the legs. Justin has built his coaching business on the principle that performance depends on mental fitness as much as physical.

‘Everything involves mental and physical integration,’ Justin says when I ask him about the Mind Matters name. ‘I’d say 95% of the training and preparation and support for athletes when I was a pro was about the physical performance: our gear, our training, strength, food.

We’d have all these ducks in a row, but things still didn’t go to plan. Like there was something missing, and for me that was the attention to the mental side of it – motivation, welfare, athlete wellbeing.’

We set off early, around 6am, and although the sun is up, it’s not really doing much. We dive straight into the Pipeline Trail across the road from the tavern. It’s not strictly gravel riding – more like easy singletrack, skirting the side of kunanyi / Mount Wellington with gentle curves on red loam, criss-crossing the big old pipe that was built in the 1860s to supply Hobart with pure mountain water – and still does.

When we emerge from the cool rainforest, we’re greeted with incredible, sunny views over the Derwent Valley before we cross back over Huon Road and, unfortunately for my soon-to-be-frozen toes, turn left down the long, gravel descent of Wolfes Road. We hook around a wild, loose corner pocked with ruts and we’re out of Hobart in an instant. The Huon Valley rolls out before us. At first I can’t pronounce it (it’s ‘hu-won’), and we all marvel that it’s so close to Hobart that in other cities it would be a suburb. But kunanyi keeps the door to the valley closed and so far most commuters are unwilling to climb the foothills and cross that threshold on a daily basis – although that’s changing.

The mainlander diaspora

When you meet a Tasmanian, the first thing they tend to say is, ‘Where are you from?’ The second thing is ‘hi’. Think about it. It’s a tiny island as far away from anywhere that you can get in this world. It’s got its own flora and fauna, its own history, its own culture. Tasmania is defined by its differences from mainland Australia more than any similarities. And now that COVID has written itself into all of our stories, Tasmania’s isolation, its littleness, its insularity, its ruggedness – these are all highly desirable to newly freed work-from-home professionals. And the city of Hobart, which looks a lot like Mosman if Mosman were flanked by Gondwanan rainforest and alpine slopes and half the price, is now the site of the Great Australian Diaspora from clogged commuter cities.

And while it’s great for Sydneysiders and Melburnians to discover the wonders of the island state, Hobart is suffering from what Justin calls ‘growing pains’. For Hobartians, house prices have skyrocketed, as have rents, as the stream of mainlanders have arrived, many of them buying up houses sight-unseen during the pandemic.

Justin and his wife Morgan made the tree-change before most, in 2018.

‘Why put yourself through big city life if you don’t have to be there?’ he says, when I ask him about moving from his native Sydney to Hobart. ‘Putting ourselves through sitting in traffic every day, and the impossible dream of ever owning a home. And my ancestors are from here. It agreed with our lifestyle. We’re both active, we love nature and the wilderness, and it made it possible for us to buy a house. It took a couple of years, but we got there.’

The bike has been key in breaking into the notoriously close-knit Hobart community – not to mention others around the world. Justin explains why: ‘Cycling is that mediator that creates such positive relationships.

It’s easy to get to know people. In Tassie, within 10 days I had mates to go riding with. Cycling makes an opportunity for you to gel into a community. That helped me integrate.’

It’s early in the ride. The pure-white Mind Matters buffs Justin gave us yesterday are still… white. Smudges of sun cream are still visible on our noses. But it’s time for the first climb of the day up a gravel road called Vinces Saddle Road to an acreage property appropriately named ‘Skye Farm’. We’re in the shadows now and my nose and eyes stream from the cold air. The gravel arcs up, steep and tough. Traction is an issue, even on my 40mm road tyres. I’ve got some generous gearing on my Norco Threshold CX bike – I’m running a Shimano Di2 with a compact 34–50-tooth crankset and 11–32-tooth cassette – but no gearing on this earth is comfortable for the final pinches before the farm.

Justin warns us about a few dodgy turns coming up and we hit the most complicated, satisfying descent of the day down a super-steep section of gravel before skidding into switchback corners that take us deeper into the Huon Valley, avoiding ruts and baby-head stones as we go. We emerge on a fast, open gravel section that we ride like a wave to a brief section on the Huon Highway, then take a few backroads to our first, last, and only brew stop for the ride.

Talking type 1

The Summer Kitchen Organic Bakery in the tiny village of Ranelagh is a hipster magnet in the middle of nowhere, as well as a daily ritual for locals and a must-visit for everyone day-tripping the Huon area. So there’s a queue. But this gives me plenty of time to choose from the hundreds of treats loaded into the front cabinet: spelt carrot cake, berry tarts, strudels, fudge brownies, gourmet pies and dozens of varieties of organic breads with that gorgeous only-in-Europe-except-also-in-Tasmania crust.

Over a brew in the bakery courtyard, surrounded by sweet treats, is as good a time as any to talk to Justin about type 1 diabetes. Justin was diagnosed as a kid and has lived with the condition for 26 years. As a pro cyclist he was a member of Team Novo Nordisk – the world’s first and only professional cycling team whose every rider has the condition. I press Justin some more about how being diabetic has shaped him and his riding philosophy.

‘To be healthy with type 1 diabetes you have to apply the same principles that lead to success as an athlete,’

he says. ‘Time management is a big one. Organisation is a big one. Being able to plan ahead yet also being able to be very present and cognisant of your sensations is huge for type 1 diabetics. You rely on your sensations to understand where your blood sugar levels are. With type 1 diabetes, listening to your body or not could be life or death.

‘So as a rider and a racer, that really entrenched in me that I needed to open a window to my body and understand where it’s at and what it’s going through. It helps as an athlete in some regard. You get to know your body a bit better. You feel the effects of overtraining more, eating the wrong foods more, getting nutrition the wrong way more, and it can be more detrimental. But the upshot is that the things that make you successful as a type 1 are the same as the things that make you successful on the bike.’

These experiences of his own body carry over into his coaching and the mentoring work he’s done with other type 1 athletes. ‘It’s a big challenge. Everyone has a challenge. Type 1 diabetes 24 hours a day, 365 days a year: that’s my challenge. But everyone deals with something. I meet people with coeliac, asthma. All these people who achieve big things. They’re people who are able to view their condition as a challenge that they can meet… not a barrier. And I tell my athletes, no matter who they are or what’s going on for them, that meeting your challenges, checking in with your body. These are big parts of achieving anything.’

My challenge is getting my legs moving again after eating a huge slice of carrot cake.

We layer back up and head off. The temperature is still in the low teens, but the sunshine is clear and bright. For anyone unlucky enough to be driving a car, this is stone chip country: rough bitumen perforated with stretches of skatey, corrugated gravel. For cyclists, it’s the closest thing to a European holiday any of us have had for at least two years. We roll out of town with a distant view back to ‘Sleeping Beauty’ – mountain ranges that together resemble a peaceful sleeping woman, hovering over our shoulders. The Huon Valley is one of the biggest cherry-farming areas in Australia. With fertile, sunny, rich soil, it’s dotted with chocolate box villages and curving roads that flirt with the river’s path. Cars sit behind us for several minutes before passing us slow and wide. Everywhere are cute houses painted in pastel colours with cottage gardens, smoke spiralling gently from their chimneys. Weathervanes. Sundials. Chooks.

Despite the gentleness of our surroundings, Justin explains to us, pointing south, that we’re at the very edge of settled land in Australia. ‘That’s Mount Field over there,’ he says, indicating a peak on the near horizon. ‘That’s one of the last places the thylacine was spotted. And beyond that, it’s wilderness all the way to Antarctica.’

Climbing home

We turn onto Glen Huon Road and swap off until we arrive in Huonville for a quick bottle refill. After a brief busy segment on the Channel Highway (not a lot of shoulder, but very civil traffic), we turn into Pelverata Road, a long gravel stretch beside the river that gradually winds up a narrow valley you would never know existed if you turned up a road that looks like someone’s driveway.

We’re leaving the valley, and the only way out is up.

A few locals had asked me if I’d be ‘doing Pelverata’, and I assume that this is it. We’re on a dragging false flat of gravel, perforated with short descents that lose all the elevation gain over and over. I ride up to ask Justin how much further, thinking we must be near the top. ‘Just a couple of kays,’ he says, ‘then Pelverata starts.’

Okay. This is not Pelverata.

The valley turns deeper, darker, narrower. Hills push up on either side of us, and small holdings hug ever closer to the river on our left. The sun disappears. When the climb eventually comes into view there’s no mistaking it. It’s a wall. Like all climbs, Pelverata has an upside and a downside. The downside is that it keeps going long after it should finish, but the upside is that it levels off to a comfortable gradient of around 7% after the initial, harrowing 700-metre heave.

At the top of Pelverata the vista has completely changed. The deep valley below us, we’re surrounded again by sunny paddocks of good grazing country. Justin tells us we’re at Kaoota, an old coal mining town with a population of about 200. It’s quiet. An old timber sign advertises a local apothecary and herbalist. It’s the kind of place where one yard is full of burnt-out, rusted cars, and the next sports a tidy hedgerow and an honesty box with lemons and hens’ eggs. Justin’s in a mischievous mood and suggests we hang a left up the rough dirt of Coal Mine Road to bag a QOM and take in the view. These both achieved, we demolish the rest of our pocket food before a smooth bitumen swoop all the way back down to the bottom of kunanyi. We stop briefly at a banged-up servo at Sandfly and buy the stuff you need on a 105km ride when the last 5km are all uphill (Coke and Party Mix), then head across the highway and into the final climb, ‘Neika’. It’s a nice one. A long, steady tap surrounded by tree ferns, moss, tiny tinkling waterfalls and forget-me-not lawns. A good climb for a chat, so I quiz Justin about this route and why he chose it.

‘This is just one of my favourite loops in the whole of Tassie,’ he tells me. ‘It’s got all the magic of Tassie. It’s proper raw cycling. You’re on the dirt, you’re in the elements, you’re going up towards 600m elevation. It’s remote, it’s hard, it’s beautiful. It’s one of the most spectacular rides I’ve ever done in this country. And you feel like you’ve achieved something by the end.’

It’s because of rides like this, says Justin, that Tasmania has produced some of the best cyclists in the world. Riders like Richie Porte, Nicole Frain, Georgia Baker and Nathan Earle, to name just a few. ‘It’s a microcosm of what Tasmanian riding’s all about. You have to be tough to ride here, so the state produces riders with real grit and determination,’ he says.

The final climb traces the same, pleasant gradient for more than 4km, and drops us off at that beacon of civilisation that adventurers across Hobart know like an old friend, Fern Tree Tavern. We grab a table next to the fire.

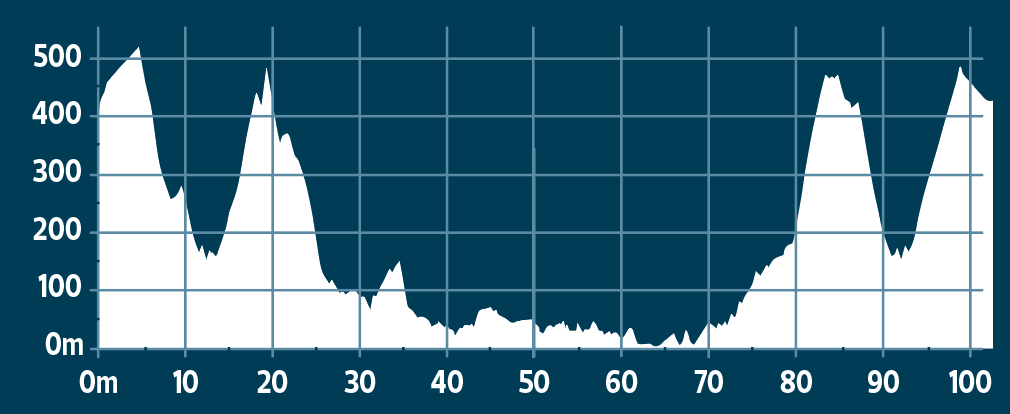

The route we took

Follow in Cyclist’s wheel tracks

From Fern Tree Tavern cross the road and head into the well-signposted Pipeline Track. After about 4km turn right onto Huon Road and take the Wolfes Road descent on the left, then turn right onto Leslie Road to rejoin Huon Road. At Sandfly, head up Pelverata Road then right onto Halls Track Road and right again onto Vinces Saddle Road for the climb to Skye Farm. At Skye Farm, continue cautiously down Vinces Saddle Road and onto Krauses Road before left onto the busier Huon Highway for about 2km. Take a right onto Dip Road and left onto Mountain River Road, before a series of doglegs through to Lollara Road and the Summer Kitchen Organic Bakery at Ranelagh. From here, the North Huon Road will take you to the cute town of Judbury. Take a left turn onto Glen Huon Road to Huonville. There is a good water stop in the parklands to the left immediately after the bridge. The Channel Highway heads south out of Huonville. After 5km, turn right at Pelverata Road, which will take you back to Sandfly with the optional summit side trip up Coal Mine Road. From Sandfly, follow the Huon Road all the way back to the Fern Tree Tavern for a well-deserved burger and chips.

The writer’s gear

I rode my Norco Threshold, which is a full carbon cyclocross bike that I have adapted for all-road riding. With the right tyres, I’ve used it for CX races, full-day bitumen epics, gravel adventures, some singletrack here and there, and the odd criterium or road race. I have a Shimano Ultegra Di2 groupset with a compact 34–50-tooth crankset and 11–32 tooth cassette to give me a wide range of gears with the super light action of Shimano’s electronic shifting. I’ll usually ride the road on 38cm bars, but have opted for 40cm bars for extra leverage and stability. I rode the Huon Valley with 40mm Maxxis Re-Fuse tyres and the gravel sections were completely worry free – in fact, on another day of this trip I rode about 15km of gravel singletrack on them and they killed it. As a slick they still roll fast enough on the tar, but the volume allows for a large contact patch with the dirt or rough Tasmanian roads. Justin reckons you can do this route on a good-quality 28mm road tyre. I chose a Lazer Genesis for MIPS protection and awesome ventilation over a pretty long day in the saddle (which eventually warmed up). While I’d normally run XTR pedals and Shimano Sphyre shoes on a ride like this, for the Huon Valley loop I chose Favero Assioma power pedals and Shimano RC300 road shoes – just for that extra bit of data for those of you who want to check my ride on Strava!

How we did it

Travel

We flew Virgin to Hobart then Ubered our way about. Hobart itself is a rideable and bike-friendly city – as long as you don’t mind climbing, or narrow bridges. If you stay in Hobart and don’t want to start this ride with an additional 10km of climbing, the handy bus route 449 will take you and your bike from town right to the Fern Tree Tavern. Bikes are $10 on top of the base fare.

Accommodation

As Tasmania’s capital, Hobart has every accommodation choice under the sun. We opted to stay in the heart of Fern Tree and chose an Airbnb.

Food and Drink

Hobart has a thriving coffee and foodie scene to explore. We enjoyed Fern Tree Tavern’s traditional, warming pub food and loved the organic goodies at the Summer Kitchen Organic Bakery in Ranelagh. There’s plenty more to explore in Hobart: head to Cascade Brewery for relaxed pub food with a side of history, or pop over to Salamanca for endless bars, cafes and street food options at any time of day or night.

Thanks to

Shimano for the sweet Di2 groupset, Lazer helmets for the protection, Maxxis for the perfect rubber, MarathonMTB for the kit, Ride Mechanic for the cleaning and personal products, and Justin ‘Mad Dog’ Morris of Mind Matters Athlete Coaching (mindmatterscoach.com) for sharing this ride and his story.