The Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan offers natural wonders and ancient treasures—and you can experience both by bike.

Words: Emma Cole Photography: Alice Gough

Day One: The Umm Qais Loop

Our first ride starts in the north of the country, two hours outside the capital Amman in a hilltop town called Umm Qais, home to the ruins of the ancient Roman city of Gadara. My cycling guide is Aref, a man whose impressive beard is matched by his jovial demeanour. He informs me that despite our route today skirting the border with Israel (or as he calls it, the area of Syria occupied by Israel) and the palpable political tensions in the region, we’re unlikely to have any trouble. I have my passport with me, just in case.

I shouldn’t have worried. The roads are mostly deserted save for the occasional farmer on a donkey tending to his sheep. Once out of Umm Qais, Aref points out the Sea of Galilee in the distance, through which the Jordan River flows on its way to the Dead Sea further south.

We begin to descend into the Jordan Valley and pass an army training base in full swing, cadets marching with weapons in arms. Aref comments that Jordan is a peaceful country surrounded by danger.

We pass olive farms and fig trees. Apparently, tomatoes are Jordan’s biggest food export—the country exports up to 600,000 tons per year, enough to fill 240 Olympic swimming pools. We slow for goats in the road, but they seem unbothered by our presence. In the town of North Shuna, Aref orders us a Turkish coffee and tells me to drink only half as it is unfiltered, so there is a thick sediment at the bottom. It’s delicious, silky-smooth and rich, and just the hit I need.

Back on the road, we turn northwards and pedal alongside the murky water of the King Abdullah Canal. A descent brings us close to the Israeli border, and we reach the first border checkpoint. While we’re not crossing to the Israeli side, guards nonetheless come out from under the shade to check our passports before waving us through.

As we head further north and east, the landscape widens out into a gaping valley with luscious shrubs above us and the Yarmouk River far below. We’re waved through a second checkpoint and begin a slow climb up a wide, beautifully tarmacked road that hugs the hillside. It’s blissfully quiet, and the views across the valley are far-reaching.

The peace is shattered briefly when we pass through the bustling town of Al Mokhaba Al Tahta, where Aref gets us some lunch of hummus, bread, olives, and tuna. It’s just the energy we need for the final climb of the day—approximately 5km and 400m of ascent to take us back to Umm Qais and a well-earned rest before our next adventure.

Day Two: Husban to the Dead Sea

A few hours’ drive south of Umm Qais is the ancient town of Madaba, which lies around 25km to the east of the Dead Sea. Today we’re riding between the two, in an area of farmland, desert, and rocky escarpments.

We start from Husban, about 10km north of Madaba, and make our way past dusty fields and polytunnels laden with the tomatoes Aref told me about. The going is relatively fast and flat, and as we speed southwards, closer to the Dead Sea, the rock changes colour slightly. Aref explains that this is because the rocks are exposed to minerals such as halite, gypsum, and potassium, which transform their appearance.

At one point, we stop in the middle of an endless vista of sandy hills, and Aref points into the distance, telling me that ‘over there’ is the Dead Sea. I have to take his word for it—all I can see is a barren landscape to the horizon. He also tells me this region is called the ‘Eye of the Wolf’ for its packs of wild dogs. I mentally prepare myself to pedal faster should the need arise.

The road dips and climbs consistently like a giant pump track, except with extraordinary views and sunshine. Eventually, the Dead Sea comes into view, sitting deep in a geological depression formed by the shifting African and Arabian tectonic plates. At 430m below sea level, it is one of the saltiest bodies of water in the world, which is how it gets its name—the high salinity means no plants or fish can live in it.

Aref informs me that the water level has been dropping by one metre every year because of increased water demand and neighbouring countries diverting the Jordan River, and if things continue, it will disappear altogether.

The village of Um Jereisat marks the halfway point, and we swing west to begin a huge 20km descent that will take us to the shore of the Dead Sea. Aref gives me a grin and launches into a series of hairpins that catapult us down through a desert landscape while a hot wind whips against our faces.

At times, the gradients top 20%, and despite some nerves about the quality of the brakes on my ageing Scott bike, I’m just thankful we’re not doing this ride in the other direction. As we descend, the rocks become more purple, the soil more beige than brown, and everything is drier.

From our start point in Husban at 800m elevation, we have descended to sea level, and in the final 5km, we just keep going deeper and deeper. Finally, we come to a halt, almost 370m below sea level and still looking down over the blue water of the Dead Sea. From our viewpoint, the mirror-like surface is almost mystical with its striking salt-rimmed shoreline. It’s mesmerising.

Day Three: Dana to Wadi Namala

For our third ride, we’re heading a few hours further south again. Our starting point is the Dana Biosphere Reserve, Jordan’s biggest nature reserve, a vast maze of limestone towers and ragged sandstone canyons that is home to hundreds of different plants and bird species. One of them—a small, yellow songbird called a Syrian serin—is so melodic you could be forgiven for thinking you were listening to The Beach Boys.

We pedal southwards along a lightly tarmacked road that affords expansive views over the Arabah Valley and its dry, rugged mountains. As ever, the Jordanian roads are reliably undulating, with a sharp climb leading directly into a steep descent before the tarmac settles into an uneven rhythm.

On leaving the nature reserve, we hit the main road of the King’s Highway. It’s long, straight, flat, empty, and exposed to the elements, so we put our heads down and ride for about 10km with only the wind turbines that loom overhead for company.

In the village of Shaubak, after about 30km, the road surface deteriorates dramatically, and Aref tells me he thinks gravel riding is sure to explode in Jordan. I agree with him while trying to gingerly navigate my skinny-tyred road bike around loose rocks for the next few kilometres.

After a brief foray back on the far better tarmac of the King’s Highway, the road tilts up again, and we reach the highest point of our three days of riding at 1,700m. From our elevated position, we take a moment to admire the brown expanse of the Arabah Valley pasted against the deep blue of the Jordanian sky. In the distance, the road meanders through a faint splattering of wind-battered trees and small gorges. Aref points to Little Petra somewhere down below. Like its more famous namesake around 10km further south, Little Petra is an ancient city carved into the sandstone cliffsides—only smaller.

It’s a magnificent descent to get there, exhilaratingly steep with some 18% gradients carving between rocky outcrops. The road surface is good now, so we can get some speed up as we sweep around switchbacks towards the village of Al Bayda.

Passing through the village, the road flattens out, and we ride into Wadi Namala, a canyon formed of smooth and rounded rocks with hues of dusty reds, oranges, and browns. Deep, winding channels lead off sideways and venture further into the canyon looming over us on either side. It’s how I imagine Mars must look, and as our ride comes to an end, I unclip my pedals, remove my helmet, and just try to take it all in.

A day in the capital

Day two’s ride starts about a half hour’s drive south of Amman, meaning Jordan’s capital is easy to work into an itinerary. Must-visits include Jabal Al Qal’a, a hilltop citadel that dates back thousands of years and includes the Roman Temple of Hercules and the 8th century Umayyad Palace. From there you can look down to the east on the city’s Roman amphitheatre, the largest and best-preserved in the country. To the west lies another highlight, the King Abdullah I Mosque, with its large blue mosaic dome and elegant stone facade.

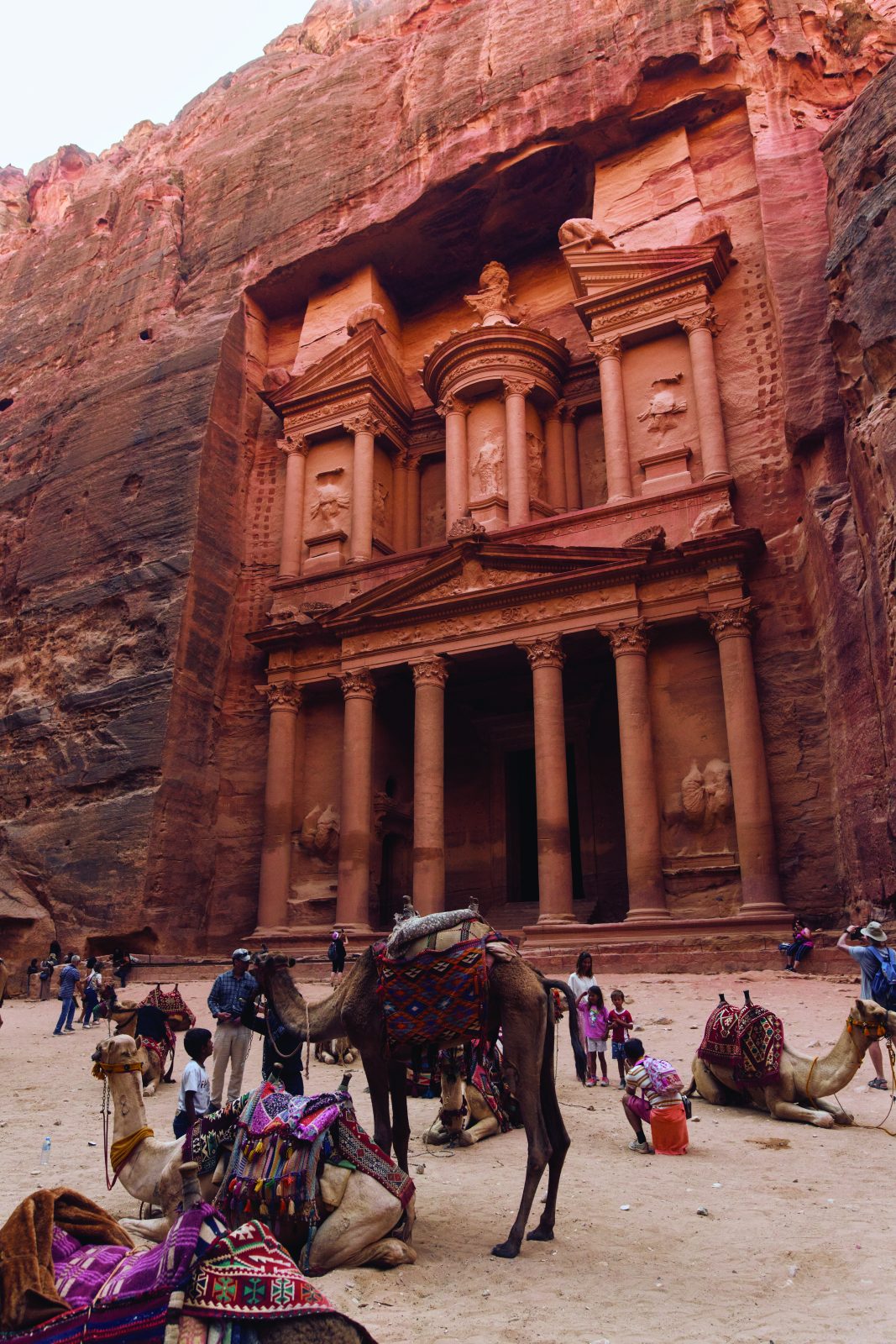

Wonders of Petra: A city carved in the cliffs

Situated in the southwest of Jordan, and a short distance from the village of Al Bayda, Petra is one of the world’s most famous archaeological sites. Created between 400BC and 106AD, it was the centre of the Nabataean empire, but after an earthquake, it lay abandoned and hidden from the outside world for centuries.

The deep gorges and towering cliff faces of Petra were the façades that the Nabataeans used to carve intricate buildings into the pink sandstone rock using iron chisels and hammers. Access is via a narrow canyon called Al Sig, making the enormity of the site’s creation breathtaking. What’s more, despite the wealth of temples and tombs, archaeologists believe that just 15 per cent of the city has been uncovered. The majority still remains underground and untouched.

How We Did It

There are direct flights to Amman from Dubai with Emirates, Abu Dhabi with Etihad and Doha with Qatar Airways. The best times of year to visit Jordan are spring and autumn, when the weather is warm but not roasting. Cyclist went in early October, which was perfect. Our thanks to Cycling Jordan and Aref for devising the routes, guiding us and lending us a bike. Also thanks to the Jordan Tourism Board for organising our trip and special thanks for Amjad for being a brilliant tour guide. For more information go to visitjordan.com.