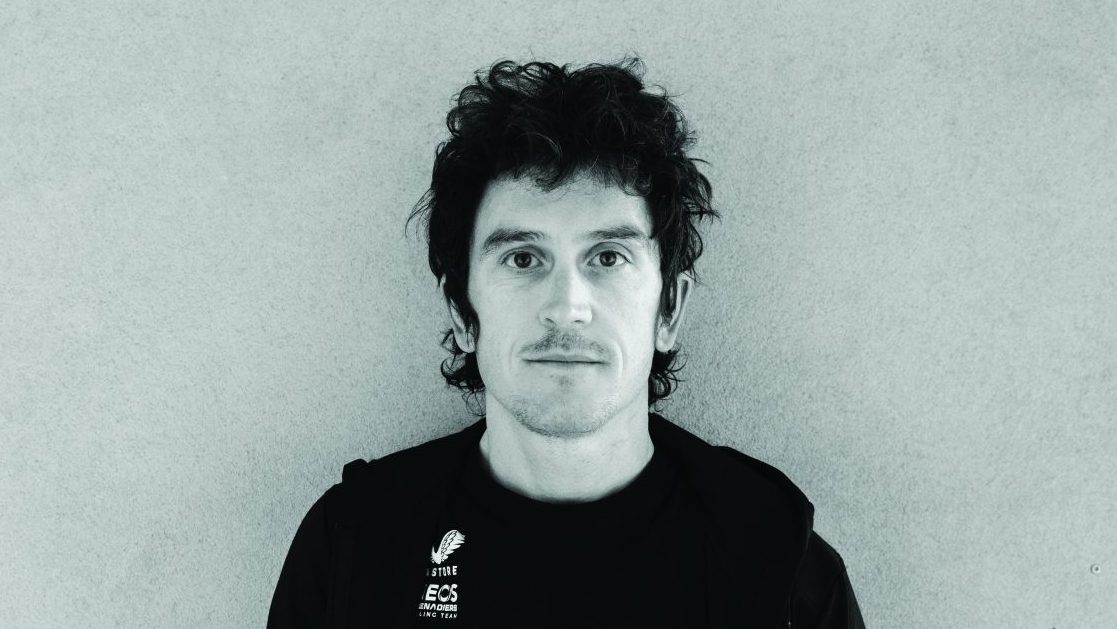

Geraint Thomas doesn’t want to sound like a grumpy old man, but after 18 seasons as a pro he has a bone to pick with all the young upstarts in the peloton.

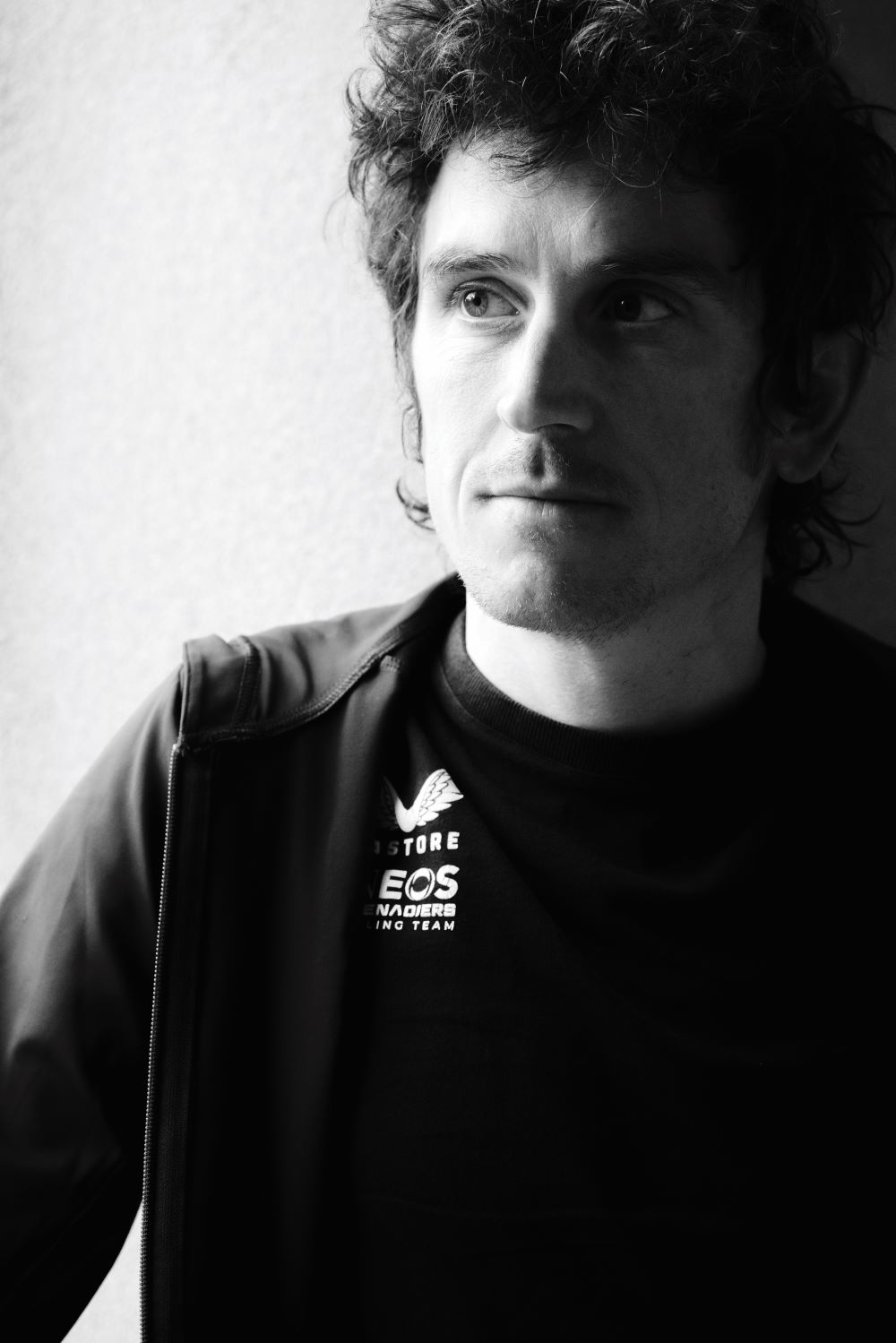

Words Jeremy Whittle Photography Alex Duffill

Geraint Thomas’s professional career started in 2007, just four years after helmet-wearing was made mandatory.

Nearly two decades on, with the 2024 Grand Tour season underway, it’s testament to his longevity that he’s still seen as a podium contender in every race he starts. Resilience, durability, strength of character – these are the traits that are now associated with him.

When it comes to commitment to the Ineos Grenadiers cause, there’s no doubting Thomas.

Right now though, he’s warming to his theme of ‘those pesky kids’… ‘I don’t want to sound like this old guy that’s berating the younger guys all the time,’ the 2018 Tour de France winner says as he relaxes one evening midway through the Tour of the Alps and before the start of the Giro d’Italia, where he’ll go on to finish third, ‘but I just feel like riders turning pro straight out of the juniors, or who’ve done one year [as a pro], they still need more of an apprenticeship.

‘They’re super athletes, they’ve got super talent, they do all these watts – bravo!’ he says sardonically of the endless stream of young talents now buzzing around at the front of the bunch.

‘But they don’t necessarily understand how to race, in the peloton, close to each other at those speeds.

That adds a bit more of an element of danger to it all.’

Danger has been a buzzword again in pro cycling of late, a little over a year after Gino Mäder’s death in June 2023 prompted much soul-searching over the extreme risks taken almost every day by the peloton.

A flurry of bad crashes in April, including a horrific wipe-out in the Tour of the Basque Country that took down Jonas Vingegaard, Remco Evenepoel, Primož Roglič and Queensland’s Jay Vine among others, have again rung alarm bells.

Thomas, unlike some, is keen not to point the finger of blame, emphasising that there is a collective need for everyone – riders, organisers, officials – to take responsibility to do more to protect the peloton. ‘It’s frustrating. Look at other sports’ safety aspects – F1 or whatever,’ he says.

‘You’re on closed circuits and it’s a lot more controlled. This sport is just totally different.’

After the Basque Country catastrophe, almost everyone with a smartphone weighed in on what needed to change.

A chicane was hastily added to the approach to the Arenberg, the most dangerous section of cobbles at Paris-Roubaix.

Some blamed the behaviour of rivals, while others lambasted SafeR, the UCI’s own safety initiative. Thomas chooses his words carefully.

‘Everyone’s talking about safety now, because big-name riders have crashed, but it has been happening for years.’

Actions not words

One of those who did point fingers was UCI president David Lappartient, who stated that ‘50 per cent of the crashes’ are down to what he called the ‘attitude’ of the riders.

Thomas was not impressed, even if he accepts that some riders do take too many risks.

‘I think Lappartient needs to focus more on the 50 per cent that he can affect, then,’ Thomas said at the time.

‘I agree with what he says but it just doesn’t make sense to me even saying it.

That means 50 per cent is still down to him and organisers to do everything they can.’

Thomas knows the stakes are getting higher and the expectations of riders are forever increasing.

Meanwhile, safety measures have failed to keep pace with gains in technology and performance.

‘Nutrition, training, equipment…’ he says, ‘we’re just going faster. Everyone is so keen and wants to get a result.

It’s a vicious circle.

Then there’s road furniture; roads are busier these days so there’s traffic-calming, kerbs sticking out, all that kind of stuff. That adds an element of danger as well.’

He admits that if he pauses to think during a race, it scares him.

‘If I thought about it, I’d be at the back of the peloton. You wouldn’t be racing – you couldn’t do it.

‘So much could be done, not just from an organisers’ point of view but from a rider point of view.

We all know when you’re younger you’re a bit more carefree.

When you get a bit older you realise it’s just not worth it.’ Asked if becoming a father in 2019 had an impact on his mentality, he ponders the question, then says, ‘Maybe a bit.

You realise there’s a time and a place.

If you’re on for winning Milan-San Remo, say, you’ll take a couple of extra risks coming down the Poggio.

I still wouldn’t be as much on the limit as Matej Mohorič was when he was almost on the deck twice going down there. I’m past that now.

‘At least on that race everyone knows the descent. But on a race like this in the Alps, 90 per cent of the guys won’t know the roads.

You’re going down these descents, flying down them.

I was talking to Adam Hansen [president of the CPA riders’ union] and we were saying that if this was a new sport, there’s no way it would be allowed.

But just because of the tradition and the, “Oh, it’s always been this way” – well, it’s not an excuse anymore, is it?’ Two days after we speak another Aussie, Chris Harper, crashes on a fast downhill and slides, sickeningly, head-first into the base of a lamppost.

The Jayco-AlUla rider lay motionless but then thankfully sat up after being tended to by horrified spectators.

Harper suffered only superficial injuries and a concussion. It was another lucky escape.

Lone voice, team player

As he edges into his late thirties, Thomas has become more opinionated and provocative than when he was racing in the tightly controlled, highly scrutinised hothouse of Team Sky.

Ironically, in the time since his team sponsor morphed from broadcasting mogul to petrochemical giant, his own media profile has grown.

His forays into creating content for his podcasts and headlining in his off-season stage shows have all made him seem that bit more comfortable in the public eye.

Thomas makes joking references to the latest crop of ‘little bastards’, as he refers (affectionately) to the likes of Evenepoel, coming through all around him.

But there are also those he regards with disdain, such as Nairo Quintana, now making yet another comeback at Movistar after some difficulties with the anti-doping authorities.

In April, Thomas and his teammate Luke Rowe hastily edited out some disparaging comments about the Colombian’s ethics after their jibes in a podcast went down very badly with Quintana’s hordes of fans.

Given his teammate Egan Bernal’s nationality, it was a rare misstep for Thomas, who has handled himself well throughout much of his career.

But then Ineos Sport is a far broader church than Team Sky and Thomas knows it: ‘It’s pretty cool to be in the same circles as F1 racing, Manchester United, [America’s Cup] sailing,’ he says, before adding, ‘You can take bits from everything.

I think that’s something to capitalise on.’ He realises too that professional cycling’s brutal nature makes it one of the most demanding of sporting environments.

‘It’s one of the sports that is the most professional,’ he says. ‘I think cycling has been ahead of most sports really.

Obviously it’s all about being physically as fit as you can be, so all those cornerstones of the sport – you have to manage them well and have a really scientific approach.

‘A lot of those principles you can take with you elsewhere,’ he adds, ‘especially guys like Dave [Brailsford] and Rod [Ellingworth].

They love cycling but at the same time they’re so hungry. Guys like that need a challenge the whole time.’

Of course, Thomas is the last man standing of ‘The Team that Dave and Rod Built’ back in the early noughties with Lottery funding, a competitive academy programme and a fierce ambition to make cycling a mainstream British sport.

His most longstanding mentor, Ellingworth, left Ineos Grenadiers suddenly at the end of last season, a dramatic departure that Thomas described as ‘gutting’ and ‘surprising’.

Ellingworth took up a role as race director at the Tour of Britain in March this year, but he and Thomas stay in touch. ‘He sends me the odd message.

We’re still in contact,’ Thomas says. ‘I was disappointed to see him go, but I get the reasoning.’

Dave – that’s Brailsford of course – is still working with Thomas as head of Ineos Sport, but has a more distant relationship with the cycling team now that he is immersed in the rejuvenation of Manchester United.

‘I get the impression Dave still massively misses the team,’ Thomas says.

‘It’s his baby really – he started it. He’s still really passionate about the sport and still massively involved.

He gives me a ring every now and then, but just has a lot of other things going on.’

Thomas maintains that Brailsford’s distance does not mean that the team’s Grand Tour ambitions have dimmed.

Another Tour de France win, he says, is top of team owner Jim Ratcliffe’s objectives. ‘Jim really wants to win the Tour.

Fair play – that is the ultimate and that’s what we’re trying to do.

In my opinion the whole team can develop and move forward in other ways, and then build towards that again.

It might take a couple of years but I still believe this team can get back there.’

So Ratcliffe’s interest is all about winning the Tour again with the team formerly known as Sky?

‘Not necessarily with Jim, but it filters down and you hear talk of the Tour a lot from senior management. But with Jim – he’s not buying Man United just to qualify for Europe. He wants to win. That’s sport in general.’

Reliving the Giro

Few who watched the final time-trial at Monte Lussari in last year’s Giro d’Italia, in which Thomas was overhauled by Roglič, will forget the experience.

The Welshman certainly hasn’t, even though he has tried.

‘It was hard,’ he admits of that afternoon’s reversal of fortune.

‘You lead the Giro for half the race and then you lose by 14 seconds on the final day.

It’s a tough one.

But then as [sports psychologist] Steve Peters would always say, “Life’s not fair. Get on with it.”’

It was a stage in which time appeared to stand still.

Thomas made a bike change so unhurried that it almost took place in slow motion.

An inspired Roglič, buoyed by a sea of Slovenians, sped upwards into the race lead.

His Welsh rival, legs leaden with fatigue, churned helplessly towards an inevitable defeat.

‘It was a tough and challenging moment, but for me it wasn’t like I had a bad day or did anything drastically wrong,’ Thomas says.

‘Roglič had a flyer and he deserved to win it.

It’s not like I lost it – he won it.’ Thomas has ridden 21 Grand Tours in his long career.

There have been other near misses, including five podium finishes in the past six years.

The hardest to take, perhaps, was his runners-up spot in Paris in 2019, behind teammate Bernal.

It was a result achieved despite a winter spent ‘socialising’ following his Tour win in 2018.

But regardless of what happens in any Grand Tours going forward, it would be foolish to dismiss his chances.

He is wise and wily, canny and cunning, a great observer of racing with an eye for opportunity.

‘I’m not one to play mind games,’ he says.

‘I’ll just keep doing my thing and will try and stay consistent and good and strong.’ Tadej Pogačar, he adds, is getting older and wiser too, though, and remains the man to beat.

‘I’m sure he’s learned from some of his mistakes,’ Thomas says.

‘When Tadej retires he’s going to be one of the greatest of all time.

It’s a big challenge but it’s one we’re relishing.’

The best of G

Road racing highlights of the first Welshman to win the Tour

2007 Signs for Barloworld and rides his first Tour de France, completing the race and finishing 140th overall

2010 Joins Team Sky and takes his debut pro win in a time-trial at the Tour of Qatar. Wins the UK National Road Race

2014 Takes the gold medal at the Commonwealth Games Road Race

2015 A strong spring Classics campaign is headlined by victory at E3 Harelbeke and third at Gent-Wevelgem

2017 Takes a first Grand Tour stage win and the yellow jersey in the Tour’s opening prologue in Düsseldorf

2018 Follows GC victory at the Critérium du Dauphiné with two stage wins and the overall at the Tour de France

2019 Finishes second by 1min 11sec to teammate Egan Bernal in his Tour defence

2022 Wins the Tour de Suisse on the way to a podium finish at the Tour de France

2023 Loses out to Primož Roglič at the Giro by just 14 seconds after leading for much of the race

2024 Finishes third overall at the Giro d’Italia, not dropping out of the podium places on GC from Stage 2 onwards

Thomas on…

…Dave Brailsford and Manchester United

‘It is kind of strange when you see him on Sky Sports sitting next to Sir Alex Ferguson or someone, but he loves it – he loves a big challenge. He goes all in.’

…one final Olympics

‘I’d love to do one more Olympics but I don’t want to go and just get a tracksuit. I want to be good enough to be in with a chance of a medal. I’ve got four tracksuits already – I don’t need another one.’