Cyclist takes to the streets of Denmark’s capital, Copenhagen, to find out what makes this ‘the world’s most bike-friendly city’

Words James Spender Photography Mike Massaro

‘Ask me how I train for hills,’ says Rikke Laursen. ‘My husband is 90kg; he hangs onto my saddle and I have to pull him up the short climbs we do have.’

It’s an unorthodox method, but it clearly works. Rikke was 2019 Masters World Champion, beating off high-altitude rivals despite living in the eighth flattest country on Earth: Denmark, average elevation 34 metres.

(Trivia buffs: the Maldives is the flattest country on the planet, just 1.5 metres above sea level.)

Along with being a highly accomplished cyclist, Rikke runs a coaching company, a coffee-cum-bike shop, a PR agency and various race teams, and from time to time commentates on Danish TV and radio.

Obviously, some people just don’t need to sleep, otherwise how else has Rikke found time to guide me round Copenhagen today?

And we’re away

As anyone who rode a bike through a big city during a Covid lockdown knows, there was the briefest of moments when the city centre was a cycling utopia.

Ever since, I’ve wondered how else this might be achieved without the need for humanity to be facing grim death.

And there is a way, I figured: just look at Copenhagen.

From the World Economic Forum to the UCI, it has been given accolade after accolade, all declaring the same thing: this is the most bicycle-friendly city in the world.

So, why is that? OK, there is the obvious argument of population; Copenhagen’s is around 660,000, while a larger European counterpart like Inner London, for example, has a population of 3.54 million.

Yet this doesn’t quite stack up, as Copenhagen isn’t exactly shy of people – population density here is 7,332/km2, compared to London at 11,098/ km2.

For context, the City of Sydney local government area is approximately 8,176/km2, Inner Melbourne is approximately 10,662/km2, and Inner Auckland is roughly the same as Melbourne.

But as Rikke and I pedal out from Copenhagen’s old town, Indre By, another reason is already obvious – the sheer number of cycle lanes.

Official sources here count 546km, most of which is segregated.

According to Transport for London, there are just 360km of similar cycleways in the UK’s capital, while Melbourne has 135km of on and off-road cycle paths.

It also might help that Copenhagen’s first cycle lane appeared in 1905.

After 5km of mostly segregated lanes, Rikke calls out for a coffee stop.

To our left, the words ‘Bosch’ and a huge cartoon sparkplug are writ large in neon, a local landmark of the achingly cool Meatpacking District, where industrial spaces like this old auto parts warehouse have been turned into funky cafes, restaurants and galleries.

Here is home to one of Copenhagen’s best coffee shops (after her own, says Rikke), which unsurprisingly given its name – Prolog – is a popular haunt for cyclists.

For the coffee snobs out there, I’m told the reason a Copenhagen flat white tastes as it does is the Dane’s use of slightly soured milk.

Coffees reduced to tide marks, we wind our way through the streets and across the Cykelslangen, whose twisting, elevated passage makes supreme sense given its translated nickname: the Bicycle Snake.

This is one of three pedestrian and bike-only bridges across Copenhagen’s Inner Harbour, a concrete and wire totem to the Danes’ love of cycling and design.

‘We think of our architects like other people think of movie stars,’ says Rikke.

We continue up the eastern side of the harbour, the Copenhagen Opera House ahead, the neighbourhood of Freetown Christiania to our right.

The former is one of Denmark’s most controversial buildings, gifted by Mærsk shipping magnates and heavily criticised by its architect, Henning Larsen, who wrote a whole book about how much he hated it.

Larsen described it as bygherreinficerede, a brilliant word meaning ‘owner infected’.

Christiania, on the other hand, couldn’t be more different.

A hippy community set up on an old military base, it enjoys a murky relationship with the city as a place where cannabis is openly sold and smoked.

It’s also where Christiania bikes are made, those wooden-box cargo trikes you may have seen transporting kids in the front.

Speaking of the kids, there’s another feather in the Copenhagen cap: local authorities, and even schools themselves, can apply for schemes and grants to lower the density of traffic in their area so as to make the school run more appealing by bike.

Copenhageners ride a bike for more than half of all journeys, from dropping off the kids to getting to work, whereas in Australia just 0.7% rode to work according to 2021 Census data (compared with 57% by car and around 33% staying at home – this was completed during Covid, after all).

We cross back over the harbour on arguably the most famous of the bridges here, Inderhavnbroen, but better known by its nickname ‘the Kissing Bridge’, so-called for the way its two halves retract and close to let boats through.

It’s also infamous with cyclists for a tight turn off the end which has seen its fair share of spills.

Apparently the locals actually quite like it this way though.

‘It means people have to slow down,’ says Rikke.

Mermaids, deers and trains

Who’s the most famous Dane? While recent years may have seen Jonas Vingegaard knock Peter Schmeichel down into third, top spot will forever be Hans Christian Andersen.

Adored by generations and venerated in Disney, Andersen has been commemorated on the edge of Copenhagen’s harbour with a statue.

Only it’s not of Andersen but of his creation, The Little Mermaid, which now stands as a Danish national symbol as much as anything else.

So much so Den lille Havfrue has twice been decapitated, has had her arm removed, her body daubed in paint, a dildo inserted in her hand and had her base blown up with explosives so as to tip her into the harbour, all in the name of political causes.

Continuing north, we pass other monuments to Denmark – the 26-metre-tall Tuborg beer bottle, Mærsk container ships, a statue of polar explorer Knud Rasmussen looking wistfully out to sea.

And, if you’re into this kind of thing, one of the most famous petrol stations in the world, the Skovshoved Tankstation designed by Arne Jacobsen and looking every bit like it has been lifted from The Jetsons – a 1930s imagining of a future that never happened.

Our turning point is the Jægersborg Dyrehave, a forest-cum-country park populated by deer and used by Copenhageners as a country retreat for walking and cycling.

In another world, another city, there would be far fewer families here with cycling kids, but Copenhagen is different.

It has the S-train, a station for which is just outside the park.

Sure, most cities have trains, and most trains you can take your bike on.

But unlike some countries, where obtaining a bike space on a train can be Kafka-esque (and that’s if there’s even one available), S-trains carry dozens of bikes at a time, in neat carriages where you can sit with your bike.

We board the train at Klampenborg Street for a few krone, and several stops later we emerge from Nørreport station via one of the largest bike parking situations I’ve ever seen.

Racks upon racks of bikes are parked dozens deep, a small sea of the things, unlike the environs of any station I’ve seen.

Immediately my non-Danish brain kicks in and I realise I have one more question for Rikke: what about bike theft? Surely that’s a problem? ‘No, not really.

The thing is, there are more bicycles than people here anyway, and really everyone has the same kind of bike, so why would you want to steal anyone else’s?’ It’s simple enough logic and, like everything I’ve seen here to do with cycling today, it just works.

Cycling city

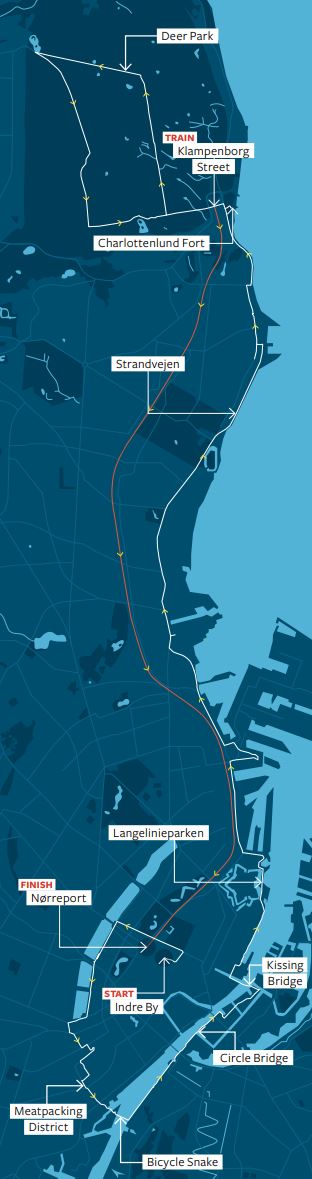

A tour of Copenhagen

Starting from Indre By, head northwest on Gothersgade towards the lake/park of Sankt Jørgens Sø.

Ride south to the Meatpacking District, stop for coffee at Prolog cafe then continue over the Inner Harbour via the Cykelslangen (the Bicycle Snake).

Follow the harbourside back north along its car-free embankment, over the Cirklebroen (Circle Bridge) then cross back over the water on the Inderhavnsbroen (Kissing Bridge).

Ride through the Langelinieparken, past the Little Mermaid statue then head north on the bike path adjacent to the O2 road.

Follow the path onto the Strandvejen, keeping your eyes peeled for the Tuborgflasken (26-metre beer bottle).

Follow Strandvejen past the Charlottenlund Fort, by the sea, where it merges into Kystvejen.

Ride up past the Skovshoved Tankstation (often mapped as Olivers Garage), past the Knud Rasmussen monument and on to Jægersborg Dyrehave (Deer Park).

Do as big a loop as you have time for, seeking out the hunting lodge in the middle, then head for Klampenborg Street station, just outside where you came in.

Ride the S-train (line C or RE) back to Nørreport station, a few streets over from Indre By.

Distance 52km (12km by train)

Total ascent 276m

Planning to succeed

An expert guide to what makes Copenhagen so bike-friendly

‘We have time on our side,’ says Niels Hoe, who has worked in urban planning for more than 20 years, including for the City of Copenhagen, and currently runs Hoe360 Consulting, specialising in walking, cycling and green mobility projects.

‘We’ve been building bike lanes for more than 100 years – but for me the biggest difference between Copenhagen and so many other places is funding.

‘When budgets are discussed here, cycling is a given like car infrastructure is a given, and municipalities don’t have to fight for one-off lump sums. That means you can plan for the future.

It also means planners don’t have that terrifying thing where suddenly they’re given €100 million as a one-off, then if anything doesn’t go right and they need to revisit it, the answer’s “no, you had your money”.

‘Another thing is people here understand the situation – there’s a huge societal benefit to cycling and the big thing is health.

People in better physical health need less care, take fewer sick days and are happier and more productive.

If you cycle a bike you effectively give the economy 7DKK [approx $1.50] per kilometre [driving a car actually costs the economy 7.5DKK/$1.60 per kilometre].

‘Often the argument is that if you take away parking outside shops and put in bike lanes then you lose business, but studies show that cyclists spend an equal amount of money.

They just shop more often, plus there is a bigger chance of running into someone you know and stopping for a drink or food and spending money that way.

‘Then the last thing: it’s obvious to Copenhageners that if you replaced the bikes with cars, things wouldn’t be very nice – the noise, the pollution – so I think even when governments change, the cycling policy doesn’t.

The people wouldn’t stand for it.’