In the first of a series on cycling’s historical artefacts, Cyclist visits the KOERS Museum in Belgium to discover the pick of the exhibits.

Words: Giles Belbin Photography: Kevin Faingnaer

It has only been a few months since Dries Mombert landed his dream job at the KOERS Museum of Cycle Racing in the town of Roeselare in the heart of Flanders. A former cycling journalist for Het Laatste Nieuws (the last story he filed was a report from the 2024 UAE Tour Women), when Mombert saw the advert for a publiekswerkerat the museum he decided to do everything possible to get the job. And who can blame him? What cycle-sport fan wouldn’t want to spend their days among this fine collection of cycling memorabilia, sharing their knowledge with visitors from all over the world?

Set over multiple floors, KOERS is housed in Roeselare’s former arsenal. Opened in 1903, the building has been used variously over the years to accommodate the Civil Guard, fire service, administration offices, a school, a volleyball club and concert hall. In 1962 the city established a folklore and local history centre here and in the mid-1980s bought a collection of historic bikes to exhibit. Interest in the cycling collection grew and in 1998 the city’s authorities decided to open a dedicated bike museum.

Over time the professional side of cycling became a bigger part of the collection and in 2018, following three years of renovations, the museum was renamed KOERS Museum of Cycle Racing. ‘Koers’ translates literally as ‘course’, but it has a wider context that is woven into the fabric of life here.

‘When Flemish people say they are going to the koers, they mean they are going to the race,’ Mombert tells Cyclist. He is explaining the museum’s history as we wander around its World Champions’ Hall, an ornate and high-ceilinged space that once housed the fire service’s gym but is now used for temporary exhibitions. Named in honour of the four Roeselare residents who have claimed at least one rainbow jersey – Benoni Beheyt, Patrick Sercu, Jean-Pierre Monseré and Freddy Maertens – today the hall is being used for weddings because the city’s registry office is being renovated.

Before the next ceremony begins, Mombert points out bikes displayed around the ceiling that chart the development of the bicycle, from a replica of an 1817 running machine through to a modern time-trial bike. In 2025 the museum is planning a temporary exhibition in this space that will cover the internationalisation of the sport. The idea is to mark the UCI Road World Championships in Rwanda, the first time the event will have been held in Africa.

‘We want to show a piece of cycling memorabilia from every country in the world,’ Mombert tells us. ‘We are busy pulling that together at the moment.’

We climb the stairs to the floor dedicated to the ‘emotional and cultural phenomenon’ of cycle racing in Belgium, reflected in colour-themed collections of various jerseys, posters and other memorabilia. We watch a specially commissioned video on the activities in a Flemish village on the day of its annual kermisand examine the evolution of a pro’s personal kit through the decades.

Then it’s off to the museum’s ‘Service Course’ where its main bike collection is housed. The machines here include a bike painted in Faema colours and built by the legendary Faliero Masi, custom bikebuilder to many a champion and nicknamed ‘The Tailor’. The bike was ridden by Eddy Merckx in 1967/68 as authenticated by the man himself – a real rarity, we’re later told.

Pick of the bunch

Siegfried Aneca, who works at KOERS as a curator, explains how the museum amasses its collection: ‘We have guidelines on whether to accept or decline items that are offered to the museum. It has to enrich the collection.’

Some of the items featured have been donated, either by the families of riders or by private collectors, while others are on loan. The museum also has a budget with which to purchase items.

‘Cycling is very popular and there are many collectors with huge budgets,’ Aneca says. ‘As a recognised museum with a permanent exhibition, it is sometimes easier for us to display an item if people want it to be shown or a rider remembered. But our budgets are not high, so we have to make choices. We search for gaps in the collection. And not only bikes, jerseys or trophies but also documentation, magazines, books…’

Indeed, the museum’s collection of published material, which runs into the thousands, includes archives of newspapers and photographers. ‘That is something unique because there are a lot of cycling museums that have bikes and jerseys but none of them collect the written aspect,’ Mombert says. ‘We try to collect a library of cycling.’

We finish our visit with a walk along the museum’s koppenmuur, a long brick wall featuring murals of riders such as Rik Van Looy, Yvonne Reynders, Briek Schotte and, most recently, Lotte Kopecky. ‘Lorena Wiebes won after a great leadout from Lotte Kopecky,’ Mombert reflects, recalling that final story he wrote for HLN. ‘Now I get to see Lotte every morning when I walk into the museum.’

1 – Rudolph Mullers 1903 La Française bike

In 1903 Rudolph Muller, an Italian who later obtained French nationality, rode in the inaugural Tour de France. The only Italian to start in Paris, he finished fourth overall, some four and half hours behind winner Maurice Garin.

‘We were contacted by a collector in France called Claude Lachot,’ says KOERS curator Siegfried Aneca. ‘For a while he lived near Labastide-d’Armagnac in southwest France, where Notre-dame-des-Cyclistes, founded by the chaplain Joseph Massie was a place of pilgrimage for cyclists. Lachot had a good relationship with Massie and many former cyclists and collected unique pieces. He had a private museum but as he got older his collection became too big to handle. In 2020 he sold us a part of it.’

Lachot’s collection included many jerseys and 15 bikes, including Muller’s bike from the 1903 Tour. ‘Muller lived in France and met Claude Lachot towards the end of his life,’ says Aneca. ‘Lachot received the bike from Muller himself so we are only the third owner of this bike. It’s a La Française and one of the oldest racing bikes we have.

You could switch from a fixed gear to a freewheel by turning the rear wheel.’ The trip to France to collect the bike provoked much interest in the Belgian media. ‘When we returned our national broadcaster was here with a film crew to record us arriving,’ says Aneca. ‘It is quite special – a bike from the first Tour de France.’

2 – Frank Vandenbroucke’s 1999 national team jersey

The Belgium team for the 1999 World Championships Road Race in Verona was a star-packed affair that included the 1996 World Champion and multiple Tour of Flanders and Paris-Roubaix winner Johan Museeuw as well as that year’s Tour of Flanders winner Peter Van Petegem. Yet the man the team backed was the rider who Van Petegem had narrowly outsprinted that day into Meerbeke: Frank Vandenbroucke.

‘Vandenbroucke was the main favourite for that race,’ says KOERS guide Dries Mombert. ‘He came into the race on the back of two stage wins in the Vuelta. It had been his best year, having also won Liège-Bastogne-Liège. So in Belgium it kind of felt like a done deal that he would win the World Championships that year.’

Yet Vandenbroucke fell early in the race. He rode on despite feeling increasing pain in his wrists and remained with the leading riders. ‘He tried to win with an attack on the final climb, but he couldn’t stand up and had to try to attack while still in the saddle,’ Mombert says. Vandenbroucke finished seventh. Later it was found he had broken both wrists. ‘

This is the jersey he was wearing that day,’ Mombert says pointing to the visible damage. Vandenbroucke, who was a god-like figure in Belgium, died in 2009 aged 34. ‘He is kind of like our Marco Pantani,’ Mombert says. ‘He was really charismatic and flamboyant. This is a really important piece for a lot of people who come here.’

3 – Josianne Vanhuysse’s 1985 Tour de France bike

In 1985 the Tour de France Féminin was in its second year. Comprising a prologue and 17 stages, and featuring climbs such as the Col du Tourmalet, it was a Grand Tour in the truest sense. Stage 5 ran for 102km from Ligny en Barrois to Nancy. Among the peloton that day was Belgium’s National Champion, Josiane Vanhuysse.

The stage finished on the 3.7km Côte de Chavigny, a climb with a maximum gradient of 7.5%. With the Dutch rider Thea van Rijnsoever up the road, Vanhuysse launched her pursuit. Catching the Dutchwoman, the two riders cooperated in the escape until Vanhuysse rode away on the final climb.‘Vanhuysse was the first Belgian woman to win a stage in the Tour de France Féminin, and this is the bike she used in the race,’ Aneca says. ‘It is even more special because she won the stage in the jersey of the National Champion.

She kept the bike at her house after her career because she won the stage on it but was not aware of its historical value.‘It was built by Eddy Merckx Cycles. The frame is steel, the wheels are from Mavic and it has a Campagnolo Record groupset. The bike was in her garage, and during a clearout Josiane was going to throw it away but her nephew said it could be of interest to the museum. Now it is one of the highlights in our service course.’

4 – Jan Ullrich’s 2003 TT bike

The 2003 Tour de France was the most incident-packed of the Lance Armstrong era. This was the year Armstrong was forced to ride across grassland on the descent to Gap; the year he suffered severe dehydration during the time-trial to Cap Découverte; and the year his handlebars snagged on a spectator’s bag on Luz Ardiden. No wonder he later said, ‘I don’t ever want to go through another Tour like this.’Going into the penultimate stage, a time-trial of 49km into Nantes, Germany’s Jan Ullrich trailed Armstrong by only 1min 5sec.

It was the closest Ullrich had ever been to the American this late in the race. It was always going to be tough to overhaul that margin, but strange things had happened at this Tour. In heavy rain Ullrich posted the fastest time at the second checkpoint, with Armstrong crossing the same mark a couple of seconds off the German’s time. Then, with 12km to go, Ullrich crashed as he navigated a roundabout, falling to the ground and sliding along the sodden road.

Any faint hope that may have flickered was firmly extinguished. Ullrich finished fourth on the stage and Armstrong had his fifth Tour in the bag. ‘For me, cycling started with that Tour and this bike,’ Mombert says. It’s a custom-built, streamlined machine designed by Andy Walser that boasted a narrower than normal bottom bracket and rear hub as well as a very low handlebar position.

‘That day I’d gone with my family to a parade but at the time Ullrich started we went into a cafe to watch. I saw him crash on this very bike. Jan will come soon to see the bike as he is planning his own museum. As a journalist it was always my dream to meet and interview him. Now that dream has come true.’

5 – Johann Museeuw’s 2004 smashed helmet

In April 2004, Belgium’s Johan Museeuw was at the end of a highly successful 17-year professional career. He’d won Paris-Roubaix and the Tour of Flanders three times apiece as well as the 1996 World Championships. At the time, Roger De Vlaeminck was the only rider to have won Paris-Roubaix four times. The 2004 edition of the race would be Museeuw’s final opportunity to join his countryman at the top of the Roubaix pile.‘He wore this helmet during that race,’ Mombert says. ‘It was his final major one-day Classic and he was one of the favourites to win.’

Early on, Museeuw, who was to retire from the sport just days later, cut a relaxed figure, even serenading Helmut Lotti – a Belgian singer and cycling fan who was riding in the QuickStep team car – as he dropped back to talk with his DS, Wilfried Peeters. As the racing heated up, Museeuw – nicknamed the Lion of Flanders – was well placed.

On the Carrefour de l’Arbre he went to work, thinning the leading group. All was going well until, on the penultimate sector, Museeuw punctured. All hope of a famous final win was over. Museeuw finished fifth and was devastated. ‘When he got onto the team bus, he threw his helmet on the floor and stamped on it in sheer frustration because he knew it was the end for him,’ Mombert says.

Lotti was on the bus and after a while quietly asked Museeuw if he could have the smashed helmet as a souvenir. ‘Johan offered me a brand new one,’ Lotti told the KOERS website after donating it to the museum years later, ‘but I insisted.’‘The Lion on the helmet is actually a print from the Lion chocolate bar,’ Mombert says. ‘Johan told me that there were some problems with the maker of the bar because of copyright. In a podcast earlier this year he said he’d like to get the helmet back but we have a good relationship with him. He often visits and helps with community-building around the museum.’

6 – ‘Allez Jempi’ collection

Jean-Pierre Monseré – also known as ‘Jempi,’ – was born in Roeselare in 1948 and turned professional with the Flandria team in late 1969. Just six weeks into his pro career he crossed the line second at the Tour of Lombardy, only to be awarded the win after Gerben Karstens, who had won the nine-man sprint into Como, failed his doping test. A little less than 12 months later Monseré was in Leicester as part of a ten-man Belgium team competing in the World Championships Road Race.

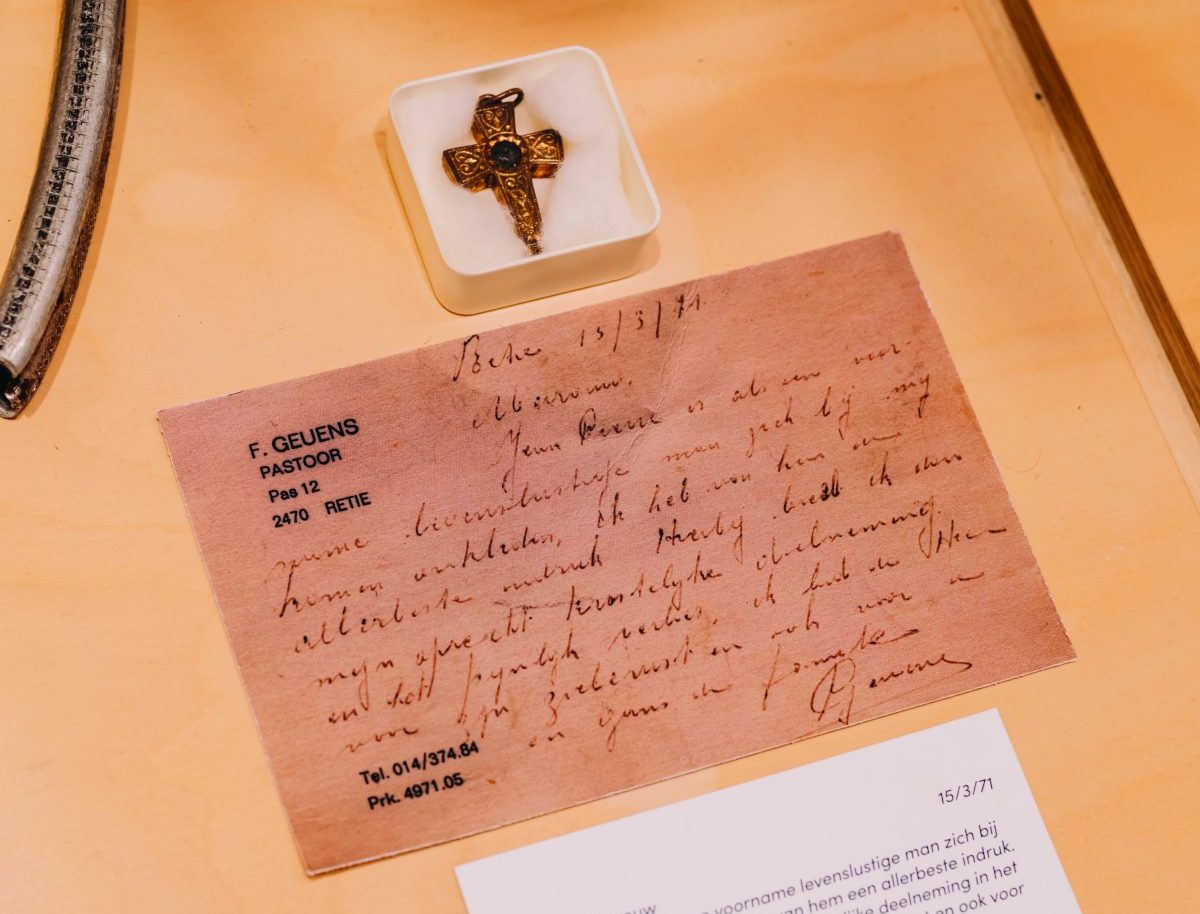

He was ever-present in the moves that mattered and finally attacked just before things came down to a sprint, holding on to a two-second gap to become World Champion at just 22 years old. Fast-forward seven months and, on 15th March 1971, Monseré was riding a kermisrace around Retie, a small town in northeast Belgium, when he collided with a car. He was killed instantly. His team manager Noël Foré was one of the first on the scene. ‘Most riders hoped for a moment that he would only be unconscious,’ Foré later said. ‘But I saw he was already dead.’

Monseré had been wearing his rainbow jersey. More than 50 years on, Monseré’s career is remembered by the museum’s Allez Jempi exhibition. ‘We have a really good relationship with the family and from time to time they pass pieces of memorabilia to us,’ says Mombert. Among the exhibits are the bicycle Monseré rode as a child, the rainbow jersey he won in Leicester and the trophy he won at the Tour of Lombardy. ‘I learned a story about that trophy only last week when Hennie Kuiper [Dutch former racer] visited,’ Mombert adds. ‘Karstens said, “They can take my name out of the books but they can’t take my trophy,” and he kept it.

Monseré’s widow frequently wrote to him asking for the trophy but it stayed in the Netherlands with Karstens’ family. Last year Kuiper reconciled the two parties and, thanks to Monseré’s widow, the trophy is here.’ Perhaps the most poignant piece on display is a small cross that Monseré wore as a lucky charm. ‘Just before the kermisin Retie, Monseré saw a priest and handed the little cross to him, asking him to make sure it got back to his wife or mother should anything happen to him. Afterwards the priest made sure the cross came back.’