Mont Caro in Catalonia may not be well known to cyclists, but that just makes this rugged, remote climb all the more rewarding.

Words Trevor Ward Photography Juan Trujillo Andrades

Pick a mountain, any mountain. Alpe d’Huez? Add three hairpins and two per cent to its average gradient.

Ventoux? Subtract Chalet Reynard and the shop at the summit. Hardknott Pass? Add 11km of distance and 1,100m of elevation.

The Galibier or Stelvio? Deduct all the motorised sightseers and overpriced fromage and gelato. What are you left with? Possibly the longest, toughest, quietest European climb you’ve never heard of – Mont Caro in Catalonia, Spain.

It’s a climb so challenging and off-the-beaten-track that the Vuelta a España has never been up it. Spain’s oldest bike race, the Volta a Catalunya, has only been halfway, stopping at a point known as El Portell, ‘The Gateway’.

The gateway to what exactly isn’t made clear, but beyond is a landscape too rugged and hostile for the modern comforts that accompany a professional bike race.

It’s the domain of Iberian ibex, wild cats, snakes, vultures and eagles, not luxury team coaches and corporate VIP enclosures.

The road is narrow, its surface neglected and crumbling at the edges. The hairpins resemble childlike squiggles rather than precision-engineered arcs, gouged rather than sculpted into the limestone rockface.

It’s a climb that is cruel and unforgiving, which rather makes me wonder why I have come back here for a second go.

Big Mig and me

It was almost exactly a year ago that I made it to the summit of Mont Caro and quietly vowed, ‘Never again.’

I turned to my guide, Santi, and told him it was nothing personal, but I’d be happy if I never saw his face again.

I returned home in a mild state of shellshock and urgently sought validation from other riders, ranging from friends to the author of a well-known series of Greatest Cycling Climbs, but none of them had even heard of Mont Caro, let alone ridden up it.

I felt like the Bible-thumping evangelist everyone crosses the street to avoid. And then I found myself interviewing a certain Miguel Induráin for this magazine (Issue 63).

Surely he’d ridden up it? ‘Si,’ he replied with those trademark sleepy eyes. And then, without further prompting, he added, ‘Es muy duro.’ It’s very hard.

Miguel Induráin, winner of five Tours and two Giros, a World Champion and Hour record holder, said it’s very hard.

I felt vindicated, even if there was only an uninterested PR person and a couple of empty drinks glasses to share my joy with.

Big Mig and I don’t have much in common but we have both ridden up Mont Caro and we both found it very hard.

And here I am, back at the foot of this mountain that I swore I’d never return to.

By now, a few more people have heard of it, or at least the bottom half of it, as El Portell was used as a stage finish in the 2023 Volta a Catalunya, when Primož Roglič beat Remco Evenepoel in a dramatic duel.

And I’m reunited with Santi, the instigator of my suffering 12 months ago, whose first words to me are, ‘I thought you said never again?’ I have no response.

I’m not sure whether it’s some masochistic trait within my otherwise uncompetitive nature that has drawn me back, or if I’m just here to see if it really was as bad as I remember.

Santi has freshened up the route since a year ago with an 80km loop that will stretch the legs before we even arrive at the start of the climb.

This might be just as well – when we leave our hotel in Tortosa the whole of the Els Ports massif, of which Mont Caro is the highest peak, is smothered in cloud.

Gentle beginnings

We cross the steel girder bridge over the River Ebro that gives a historical snapshot of the town – the 18th century façade of its cathedral, the imposing castle above that is now a luxury hotel, and the bizarre, contemporary sculpture in the middle of the river that was commissioned by Franco to commemorate his victory here in Spain’s brutal civil war and has divided local opinion ever since.

We hug the north bank of the Ebro until the buildings, noise and traffic of Tortosa have been replaced by olive groves and birdsong.

Santi points out pine, almond and oak trees before we arrive at the first climb of the day, which leads us to the Coll de Som at the dizzying altitude of 189 metres.

The descent reunites us with the Ebro, its silvery mass arcing lazily in front of us.

We eventually cross it on a modern bridge – the first we’ve seen since leaving Tortosa – before Santi announces a brief detour to the village of El Pinell de Brai and its Catedral del Vi, a stirring edifice of brickwork and mosaics housing a winery that was designed by a protégé of renowned Catalan architect Antoni Gaudi.

After passing through a narrow, pink-tinged limestone gorge, we emerge onto a plain where rows of vines extend to the distant mountains.

The main grape of this region, says Santi, is the garnacha blanca, which I shall have the pleasure of becoming better acquainted with later.

A huge, ornamental barrel bearing the name ‘Bot’ welcomes us to the next town, where the number of tractors and wine cooperatives are reminders of what powers the local economy.

The final climb before lunch is a real treat – 5km of gently rising road that winds through pines before emerging onto a balcony overlooked by pyramids of limestone.

The only other traffic is a van from the local council’s highways maintenance department that seems to stop to admire the views almost as often as us.

We plunge down to the village of Prat de Comte – ‘It’s always windy here,’ says Santi by way of explanation for the lack of outdoor tables at any of the bars we pass – and stop for lunch inside a gloomy place where the dishes of the day are scribbled in pen on a folded sheet of A4 paper but the food is worthy of a gilt-edged, leatherbound menu.

The main course

All these distractions – the scenery, the villages, the incredible food – have been welcome but I still have a gnawing sense of dread I can’t shake off.

I know the toughest part of the day is still to come. Knowledge is fear. It’s not long before we’re back in Tortosa and preparing to start the climb I vowed I’d never do again.

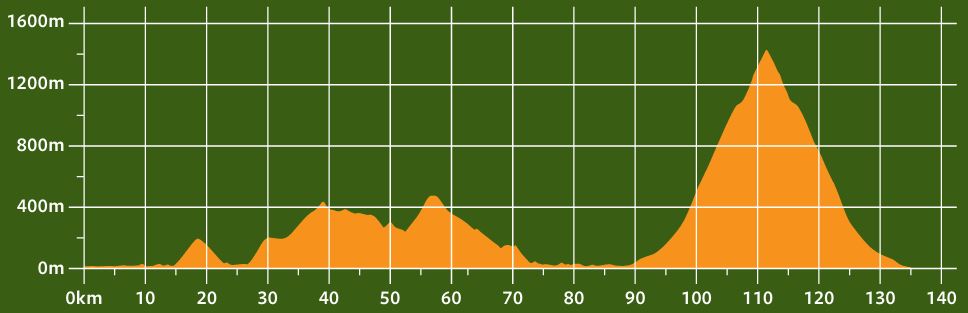

On paper, it sounds a reasonable proposition: sea-level to 1,441m in just under 24km.

The ‘categorised’ part doesn’t begin until after 10km, and from this point – marked by a ‘0km’ signpost – the gradient hovers around 10% for the next 13.8km, peaking at 18% within touching distance of the finish.

These details have been ingrained in my quads as much as my mind since my previous visit. I can’t un-know them.

Just as you never get a second chance to make a first impression, I can never again be blissfully ignorant of what this climb has in store.

Santi tells me he has ridden it three times since we climbed it together. I don’t know whether he’s expecting my pity or admiration.

We arrive at ‘0km’ just as the first drops of rain start to fall. A wreath of cloud clings to the upper slopes.

The air is significantly cooler than it was 12 months ago and I’m hoping this will be to my advantage.

Call of the wild

After about 5km there is a rest area with a fountain, the only source of drinkable water on the whole climb. Ignore it at your peril.

Shortly afterwards, looming out of the crevasse on our right and seemingly floating on the mist, a stone sculpture of a wild goat is, it transpires, perched on the top of a 100-metre pillar of rock.

Santi tells me it’s the work of a local artist dating back to 1972 but he has no idea how it was transported to such a precipitous plinth.

Meanwhile, the road keeps rising and we arrive at the set of hairpins that will deliver us to El Portell.

These hairpins, unlike the ones we will encounter further up, have been designed and engineered with a degree of sympathy for those who will be using them, and pedalling around each one almost feels like a breather.

We stop at El Portell to look back down on where Roglič and Evenepoel did battle at the Volta a Catalunya. The rain has stopped and the cloud appears to be breaking up.

We haven’t passed any other traffic, either motorised or pedal driven, and the only sound we can hear is a cat miaowing.

We scour the rockface but can’t see any sign of Tiddles. Santi, who has six cats of his own at home, shrugs his shoulders and says it must be a wild cat.

I’d be pretty wild too, I think, if I was stuck up here all alone at the gateway to Hell. We clip back in and ride through the ‘gateway’ where professional bike races dare not go.

‘You remember this?’ asks Santi with a mischievous grin that can only mean something unbearably nasty is coming up. Suddenly, yes, I do remember.

Of all the hairpins on all the mountains in all the world, this one is surely the most gruesome. It curls around to the left with such unrelenting, gratuitous steepness that I want to swap cleats for crampons.

It’s exactly the point where I felt all hope evaporate a year ago. I claw my way around its outer edge knowing that if I can make it past this point there will be less than 4km to go.

Unfortunately, I also know that the gradient won’t dipbelow double figures for those 4km.

We grind upwards, Santi occasionally disappearing into patches of dense mist.

By the time we arrive at the wooden viewing platform at the top, we are completely consumed by cloud.

There is nothing to see other than the spectral form of the telecommunications mast that this road was built to service.

The views across the Ebro Delta as far as the Balearic Islands and the Pyrenees that I remember from last year have been cruelly denied us after so much effort.

As we layer up for what is destined to be a cold descent down the same road back to Tortosa, Santi says to me with another cheeky smile: ‘Same time next year?’ I’m about to reply, ‘No chance’, but then the warm glow of achievement coursing through my body makes me say, ‘Never say never.

To hell and beyond

Follow Cyclist’s route beyond ‘The Gateway’ to the summit of Mont Caro

To download this route, scan the QR code. The route starts in Tortosa and heads north, with the river Ebro on your left, over the Coll de Som as far as Gandesa.

It then loops back to Prat de Comte, which has several bars/restaurants for lunch.

If you like, follow a Via Verda (green way) bike path along parts of the Ebro back to Tortosa, then follow signs to El Ports National Park and Mont Caro.

By the numbers

Some massif stats

1,441 Metres climbed from Tortosa to Mont Caro

18 Maximum gradient of climb in per cent

1 Number of wild cats heard but not seen

24 Number of hairpins on Mont Caro

4 Number of times Volta a Catalunya has used (part of) Mont Caro

20 Visibility in metres at the summit

0 Number of cafes, bars or shops on the climb

Bombs and bikes

Tortosa’s history from war to professional cycle racing

The town of Tortosa has hosted the Volta a Catalunya 69 times during the race’s 113-year history, mostly during the 1940s and 50s when it was still reeling from some of the fiercest fighting of the Spanish Civil War.

Author Ernest Hemingway reported from the town after it had suffered intense bombing by Franco’s Nationalist forces. A cycling fan, Hemingway described the circling aircraft as having ‘the mechanical monotony of movement of a quiet afternoon at a six-day bike race’.

In a dispatch from a different frontline – France during World War Two – the author would write that ‘it is by riding a bicycle that you learn the contours of a country best, since you have to sweat up the hills and can coast down them’.

The Volta a Catalunya, meanwhile, has used Mont Caro only four times (and only its first 8km, as far as El Portell), with Primož Roglič winning there most recently in 2023.

Previously, Alejandro Valverde won there in 2017, while Colombians Alirio Chizabas and Lucho Herrera were the victors in 1985 and 1991 respectively. In 2021, Basque rider and three-time Tour de France podium finisher Joseba Beloki successfully ‘Everested’ Mont Caro, though even he only rode up to El Portell.

How we did it

Travel

The nearest major airport is Barcelona, from which it is around a two-hour drive to Tortosa. There are regular buses from the airport to Tortosa with HIFE (hife.es), and bike boxes are welcome.

Accommodation

Cyclist stayed at the SB Corona Hotel (hotelcoronatortosa.com), a short walk from the river and the centre of Tortosa. Rooms are spacious, the restaurant is excellent and there is a swimming pool, but best of all the hotel offers secure bike storage, a workshop and washing/dryer machines for your riding kit. It can also arrange bike hire.

Food

The hotel restaurant offers excellent Catalan dishes such as grilled octopus, and wines such as garnacha blanca from the vineyards of the Terra Alta we rode past. A short walk across the river in Tortosa is Bar Restaurant Cristal, where traditional tapas has been taken to new heights by Barcelona mad chef Jordi. The tuna tartare and grilled steak are superb.

Thanks

Many thanks to my co-rider, Santi(ago) Santamaria Palacios, who plotted our route and who was a patient and knowledgeable guide. Thanks also to Josep Rodrigo Panisello, the manager of our hotel, keen cyclist and a proud Catalan who drove our photographer and arranged my bike hire. Finally, thanks to Albert Folch Giró and Carlos Llorca Margelí at Tourism Terres de l’Ebre, who arranged all the logistics of our trip.

For more information about this region of Spain, see terresdelebre.travel