On an island with year-round sunshine, water is a precious commodity. Thankfully, this ride on Gran Canaria has a climb that is sure to turn on the waterworks

Words Nick Christian Photography Patrik Lundin

What the hell is water? This was the question the late American novelist David Foster Wallace posed in 2005 in a commencement speech to the graduating class of Kenyon College, Ohio.

For Wallace the rhetorical purpose was not to get the students to consider water per se, but to encourage them to appreciate the extraordinary in the everyday.

It’s something I find myself contemplating as I stand under a shower so powerful that it is not only blowing away the cobwebs but exfoliating more than a good few skin cells.

A morning shower is something I would normally take for granted but on an island where it rains so little, this thunderous stream feels decadent to the point of indecency.

Sitting at the same latitude as the Sahara Desert, Gran Canaria gets only a handful of rainy days a year, even in winter.

This makes it a good place to consider the extraordinary nature of something as everyday as water.

It also makes it a great place to ride a bike.

Up and away

We set out from the town of Arucas in the north of the island.

My guide for today, Eva, has selected the San Juan Bautista church as the official starting point, its three tall towers and neo-Gothic façade making it impressive and foreboding in equal measure.

Far more inviting is the nearby Destilerías Arehucas, the local distillery, renowned for making rum of the highest quality.

I note that tours of the facility start at 9:30am and can’t help suggesting that we sneak in for a snifter.

On second thoughts, with 122km and 3,387m of climbing to come, perhaps some 80% proof spirit isn’t the best option for a warm-up.

As if to drive home the point, we have barely left Arucas before the road tilts upwards and we find ourselves on a 3km haul to the village of Buenlugar, followed by a short descent through Lance (no relation) and onto another climb that continues upwards for a full 23km to Monte Pavón.

Fortunately, at this early stage of the ride the gradients are gentle enough that they can be tackled without going too far into the red, so we are able to enjoy our surroundings, which are surprisingly lush for such a dry island.

The flora includes eucalyptus, stevia, aloe vera and agave growing by the roadside, not to mention the fearsomely named dragon trees with their spiky leaves. After an hour we top out at 1,200m.

The reward for reaching Monte Pavón is an expansive view over the Agaete basin, teeming with orange groves and coffee plantations.

Eva directs my gaze still further, out across the sea to where Tenerife lies glistening in the distance.

The morning we’ve been graced with is so clear that even 70km away the hazy outline of Mount Teide is visible.

From here we continue our journey inland for a thrilling rollercoaster run of around 10km down to the edge of the Los Pérez reservoir, which is followed soon after by the Lugarejos and Las Hoyas reservoirs, each plugged by a sizeable dam.

Eva informs me that these are just a few of the many reservoirs dotted around the elevated central area of the island, and that between them they capture around 35% of the water that falls on the island.

I feel marginally less guilty about my Niagara shower this morning.

Boys don’t cry

I have been warned about the Valley of the Tears.

One account I read prior to this trip described it as the ‘most notorious climb’ on the island.

Of course, notorious is a relative concept, with one person’s nightmare climb being another’s mere bump in the landscape, so I have taken the precaution of examining the Valley of the Tears’ profile on VeloViewer.

It’s numbers – 12km at an average gradient of 7.9% – give me no cause for concern.

I’ve tackled worse and, sure, it might look offensively steep from where I’m standing, high on the other side of the valley, but really, what’s to worry about? What is it they say about pride coming before a fall? As we begin our descent into the valley, Eva points out the thin streak of something vaguely resembling a road carved into the rock on the opposite side.

Doubts begin to form and I silently instruct myself to make the most of this brief period when the slope is in my favour.

Building up a decent head of steam also seems like the prudent approach, so I aim to carry as much momentum as possible (psychological, more than actual) into the climb.

A small bridge over a dry riverbed provides the only bit of flat ground between the descent from the reservoirs and the start of the Valley of the Tears climb.

Eva informs me that her bike’s gearing is poorly suited to the gradients ahead and encourages me to push on.

It shows a slightly misplaced belief in my abilities as a climber, and we’re still together as we pass through a tunnel of rock at the edge of the Presa del Parralillo reservoir and climb up the set of steep hairpins that leads up to a rocky ridgeline.

As I grind against the increasingly savage gradients, I begin to doubt VeloViewer’s veracity.

At the very least, it becomes clear that you can’t learn everything you need to know about a climb from mere numbers.

It doesn’t help that the sun is now at its most menacing and there’s little in the way of shade or distraction to soften the blow.

After the early switchbacks, bar a few brief deviations the course makes a beeline directly up the Carrizal Ravine.

The pitches seem to rear well above the prescribed average and the path is so narrow that there is insufficient room to lessen the gradient by zigging and zagging.

It’s a battle between will and wall.

Valleys and villages

Eventually will wins out.

Head down, pedals turning, I achieve something resembling a rhythm and even manage the occasional stretch out of the saddle, swinging the bike from side to side to engage every available muscle.

After several false summits, the road really does rise no more.

I haul myself over the crest and celebrate by guzzling the final dregs of warm water from my bidon.

We still have one more peak to overcome, but after the Valley of the Tears the next one holds little fear.

To get there we first have to descend a winding road that takes us beneath Roque Nublo, an imposing 80m finger of rock perched on an outcrop that was once an ancient place of worship for Gran Canaria’s aboriginal natives.

The descent signals a transition from the island’s dusty southern area into its lusher, tropical northern zone, and I can almost feel the change in climate as I attempt to hold Eva’s wheel while she carves through the twists and turns at speed.

The village of Tejeda lies at the foot of the final climb.

It’s a muddle of whitewashed houses with terracotta roofs clinging to the hillside, and in Eva’s opinion it is the prettiest village in all of Spain.

I’m in no mood to disagree.

From there, the 7km climb to the village of Cruz de Tejeda is on smooth tarmac and has forgiving gradients, but still proves to be hard on weary limbs.

It delivers us to the highest point on the ride at 1,509m, and with it comes the satisfying knowledge that it is nearly all downhill from here for the last 20km of our ride back to Arucas.

Tight switchbacks test the brakes but there’s no urgency on our part, so we drift lazily back towards civilisation, enjoying the vibrant municipalities we thread through along the route.

These include Valleseco, which means ‘dry valley’ but which is actually nestled into a green hillside, and Teror, which I can only assume is named after the rich earth here, and which boasts a pretty square dedicated to the Virgen del Pino (an image of the virgin Mary having appeared in a pine tree in 1492).

Before long the dark shape of the Arucas church appears in the distance, looming benevolently over the lower, lighter buildings nearby. It lifts my heavy legs and I take a last swig from my bidon.

To the west I can pick out the distillery’s tall chimney with AREHUCAS running from top to bottom in bold white letters.

An extra burst of power carries us through the final roundabouts and returns us to the spot we left several hours and 122km ago.

Now, about that drink.

Sweat and Tears

Follow Cyclist’s route into the rugged heart of Gran Canaria

To download this route click here!

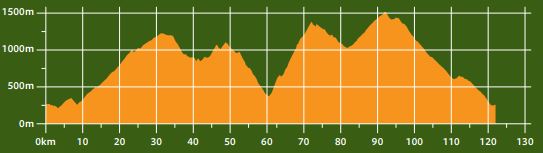

The route starts in Arucas in the north of the island and heads west to Moya before turning south and climbing to Fontanales.

A lumpy descent via the GC-217 and GC-210 takes you to the start of the Valley of the Tears.

Climb eastwards for 12km before turning north and descending (with views of Roque Nublo) to Tejeda.

After a 9km climb it’s all downhill, via Valleseco and Teror, back to Arucas.

By the numbers

Go figure

›122 Length of ride in kilometres

›1,509 Highest point on ride in metres

›3,387 Total metres of climbing

›11.9 Length in kilometres of the Valley of the Tears climb

›7.9 Average gradient in per cent of the Valley of the Tears

›20.1 Maximum gradient in per cent of the Valley of the Tears

›19 Average temperature in degrees Celsius in December

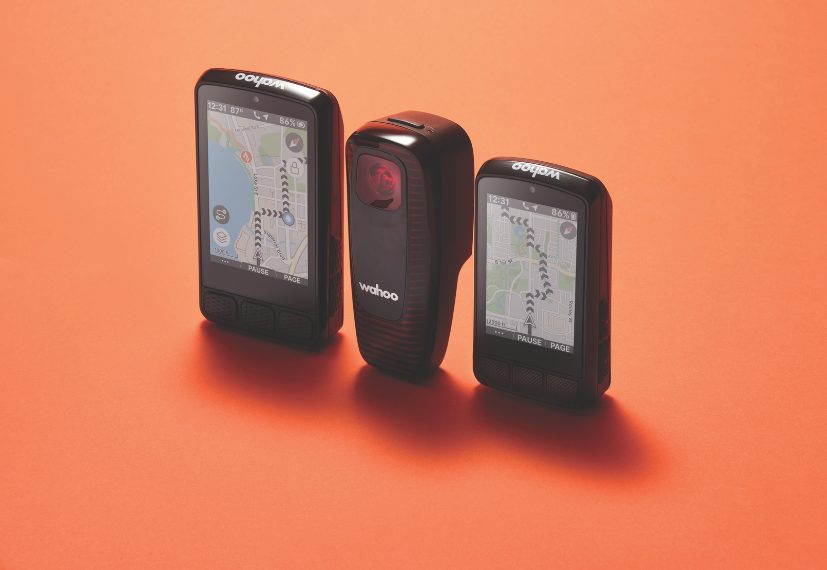

The rider’s ride

Specialized Tarmac SL7 Expert, $7,999, specialized.com/au

The Tarmac SL7 has since been superseded by the SL8, but that simply means that you can bag yourself a bargain if you’re not worried about having the latest version.

This bike was more than $2,000 dearer previously, but nonetheless still represents a sweet spot in the Tarmac range between accessibility of price and quality of spec.

Like all Tarmacs, the SL7 blends the lightness, aerodynamics and handling of a race bike with enough comfort to see you through a long day in the saddle.

And while it’s almost $12k cheaper than the top-spec S-Works SL8, it doesn’t skimp on components, coming with a Shimano Ultegra groupset, integrated bar-stem and a set of nifty Roval C38 carbon wheels

How we did it

Travel

Reaching Gran Canaria from Australia is a bit of a mission, but a mission well worth it. You’ll be facing two stops no matter which way you cut it, but your main airlines to look at are British, Qatar, Etihad and Swiss Airways.

From the airport on the east of the island, it’s about a 20-minute drive to the capital, Las Palmas, in the north, and the same to the resorts around Maspalomas in the south.

Accommodation

Despite starting this ride in the north of the island, for most of our time on Gran Canaria Cyclist stayed in the south, where there is a wealth of hotels and resorts.

The first part of our stay was at the Gloria Palace San Agustín Thalasso & Hotel (gloriapalaceth.com), which has a pool, plenty of dining options and on-site bike rental and workshop.

The second part was at the Resort Cordial Santa Águeda (becordial.com), a sprawling resort with an infinity pool, restaurant and supermarket.

Thanks

Thanks to Ana and Carmen at Gran Canaria Tri, Bike & Run (grancanariatribikerun. com) for organising transfers, accommodation and bikes, and to Eva for designing a route that was challenging but not too challenging, as well as for being a fountain of knowledge about the region.