The whats, whys and what-on-earths of bottom bracket standards

Words Charlotte Head Photography Tapestry

Bicycles may seem like simple machines, but their design is changing constantly.

New tube profiles, frame materials and levels of integration appear at a staggering pace and, while that’s all well and good, it is often the less glamorous elements of innovation that can have the biggest impact on the bikes that we ride.

While most of us will have a cursory knowledge of a bottom bracket and how it functions, it’s easy to disregard as a realm for nerds and mechanics, so we thought it was time to demystify the humble BB and explain what all the fuss is about.

The primary function of a bottom bracket is to facilitate the rotation of the cranks, which transfers power from your pedals to your drivetrain.

To that end, bearings are needed to allow the cranks to move freely.

While that is the basic principle, the factors affecting bottom brackets have become increasingly complicated over the years in the quest for peak performance and efficiency.

Nowadays, it’s not only the bearings but also the shape, structure and size of the bottom bracket area – known as the bottom bracket junction – that are subject to endless tweaks and refinements.

Factors at play

If the key purpose of the bottom bracket is simply to allow the cranks to rotate, the sheer number of different BB standards these days may seem bewildering.

This isn’t out of some perverse masochism on the part of bike manufacturers, however.

Rather, it signifies the large number of elements at play and differing ideas about how best to reconcile them.

While racy frames have become ever stiffer in the quest for ultimate performance metrics, these developments have focused heavily on the bottom bracket junction as the area where riders drive power through their frames, and thus the area where the most power could potentially be lost.

This has seen many frames develop bigger or burlier bottom bracket junctions to counteract torsion.

But in recent years, the trend towards both bigger tyre clearances and bigger chainrings has seen the bottom bracket junction needing to strike a balance to allow space for both while maintaining its own integrity.

Throw welding sites on metal frames, bike assembly, repairability and bearing longevity into the mix and the complexity of the bottom bracket area becomes more understandable.

As such, when it comes to the different standards, it’s probably best to start at the beginning…

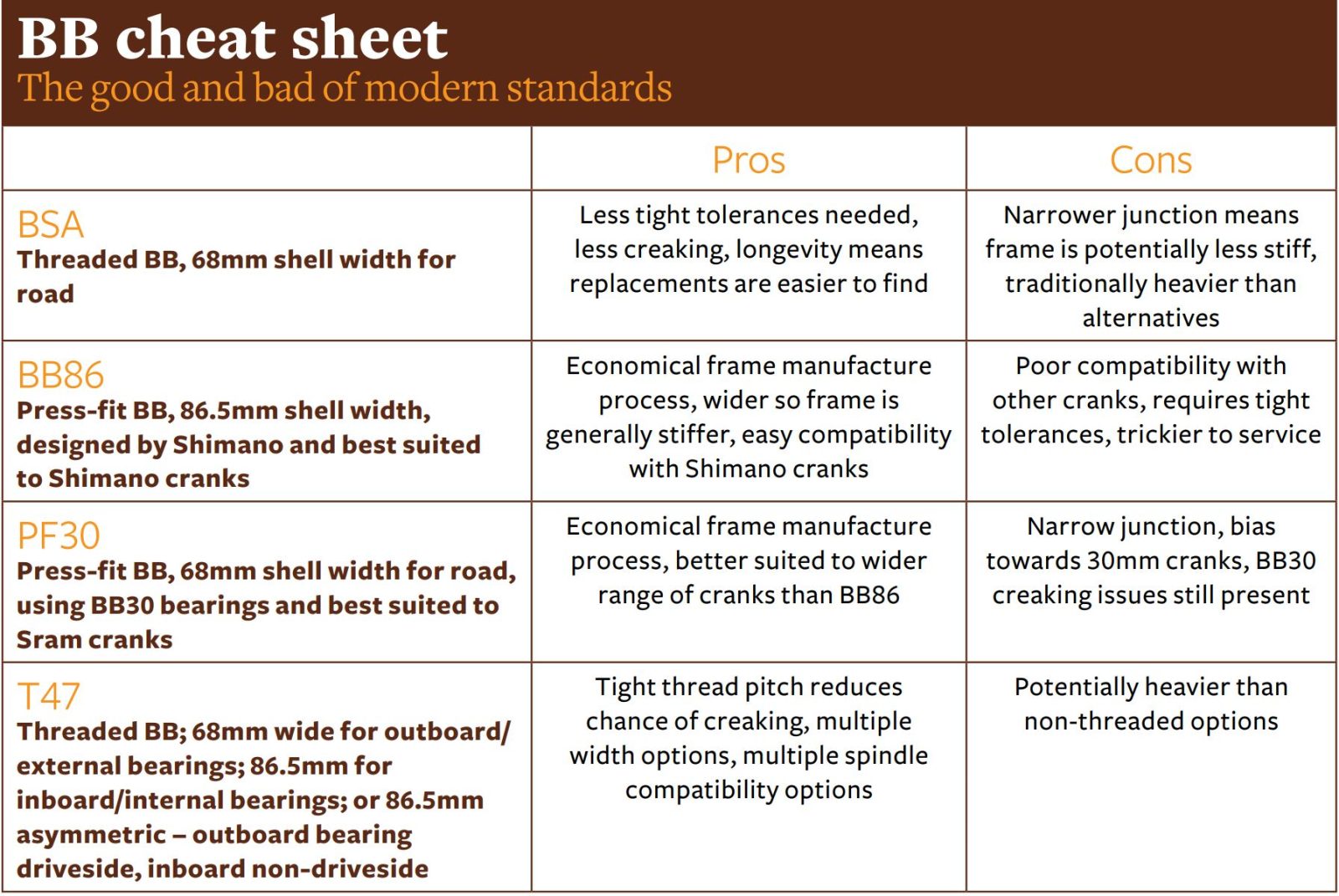

BSA

One of the oldest bottom bracket types still in use today is the BSA standard – sometimes known as BSC for British Standard Cycling.

BSA actually stands for Birmingham Small Arms, a name that Peaky Blinders fans will be familiar with, referring to the UK Midlands-based arms manufacturer that created the thread standard used for the BB cups.

Like the fictitious Shelby family, the BSA bottom bracket is widely renowned and, despite dating back in various forms to the early 1900s, endures to this day and has experienced a resurgence in recent years.

BSA bottom brackets are threaded, with both cups tightening in the direction of the rear of the bike.

While they lost favour throughout the 2000s as other standards became popular, big brands such as Specialized have recently reverted to the BSA standard.

‘Previously we made our own S-Works cranks and found the best bottom bracket for that was BB30,’ says Specialized’s road and gravel leader, Stewart Thompson.

‘But when groupset manufacturers started saying you had to use their chainrings, that’s when we migrated towards BSA.

We figured out that we could actually make frames lighter with BSA.

It also allowed us to use the lightest and best bottom bracket for Shimano cranks at the time, which we saw as the default groupset manufacturer.’

Whereas previously BSAs required a threaded metal sleeve in the frame, Specialized developed a method that allowed the metal threads to be co-moulded during the fabrication process.

The shell needed for BB30 was larger and required more metal, so switching to BSA, with its smaller bearing diameter, allowed a slightly lighter setup.

But what is BB30 anyway, we hear you ask? Sit tight, we’ll come back to it.

BB86

BB86 – also known as PF41 – is the Shimano standard for press-fit bottom brackets, introduced in the early 2000s and, as the name alludes to, generally 86.5mm wide.

Whereas BSA bottom bracket cups thread into the frame with the bearings sitting outside it, press-fit BBs have smooth external cups that are pressed directly into the frame, with the bearings sitting inside the cups.

‘BB86 works really well for Shimano because it’s designed with its system in mind,’ says WheelsMFG senior sales manager Dan DePaemelaere.

The larger shell creates the potential for more frame stiffness as there is a larger surface area, and the system is traditionally lighter than threaded alloy cups.

With press-fit bottom brackets, the margin for size discrepancy between cup and frame bore – known as the tolerance – is very low because the parts need to fit together almost perfectly to prevent creaking.

‘The plastic cups are designed to absorb some of the tolerance issues,’ says DePaemelaere. ‘Plastic is more forgiving than metal or carbon.’

Dreamed up by Shimano for its 24mm axles, it is unsurprising that conversion to other crank designs posed a bit of an issue, particularly when it came to Sram’s stouter spindles.

‘Trying to adapt a shorter 29mm spindle to a 41mm deep, 86.5mm wide shell is not an easy thing to do and, while there are solutions out there, they’re not ideal,’ says DePaemelaere.

This cup/spindle combination necessitates slimmer bearings, thus smaller ball bearings.

Being smaller, the contact area between the spindle and inner bearing race is more concentrated and, as this oversized spindle is made of soft aluminium, spindle wear becomes an issue.

While brands such as Giant, Canyon and Scott still champion BB86, many others are moving away from the standard.

An evolution of BB86 was introduced by component company FSA in the form of BB386EVO, which uses the same 86.5mm shell but also accommodates a 30mm spindle.

Given that BB86 was largely supported by those with a brand allegiance to Shimano, this new standard, focused more on a 30mm spindle, remains limited in usage.

BB30

Herald of innovation and all things novel, Cannondale introduced the then-wacky concept of BB30 in the early 2000s.

In BB30’s case, bottom bracket cups were eschewed in lieu of bearings that pressed directly into the frame, and which were designed to take a 30mm spindle.

‘Cannondale was the main disruptor of BSA,’ says CeramicSpeed’s head of product management, Paul Sollenberger.

‘There was a high focus on tolerance, where the bearings had to fit perfectly into the frame, and you could run that oversized aluminium [crank] spindle.’

The larger diameter allowed the spindle to be made of a lighter material while maintaining the same stiffness, and improved weight was an easy metric to show as an advantage.

But, while tolerances were somewhat of an issue for BB86, they were taken to a whole new level for BB30.

‘Whereas bearing manufacturers like ourselves can measure down to 0.001mm, frame manufacturers may measure tolerances to 0.1mm to keep the manufacturing process economical,’ says Sollenberger.

As a result, the BB30 standard became notorious for ‘migration issues’, where even small amounts of bearing movement resulted in excessive creaking noises.

Even its innovator, Cannondale, has since transitioned back to other standards.

PF30

Sram tried to rescue the BB30 concept towards the end of the decade with the PF30 derivation.

In essence it combined BB30 bearings with the press-fit concept of BB86, placing big bearings inside a press-fit shell.

It allowed those who wanted to use the chunkier Sram cranks to do so, while keeping the claimed benefits of a press-fit system.

As cups were used, there was less focus on the exacting tolerances required of BB30, while still allowing the same level of stiffness and crank compatibility.

‘In an assembly line of bikes, pressing in [as opposed to screwing in] a bottom bracket is very simple, and so is quicker and cheaper to do,’ says Sollenberger.

But as with BB30, tolerances were still an issue, and creaking continued.

T47

There have been many other bottom bracket standards along the way, such as Trek’s BB90 (a wider version of BB30) and Cervélo’s BBright (an asymmetrical version of PF30), each with its own strengths and pitfalls, but one of the latest developments that seems here to stay is T47.

The ‘T’ stands for threaded, while the ‘47’ denotes the specific thread pitch – meaning the gap between each thread spiral.

The standard was dreamed up by a working group including Chris King, White Industries and Argonaut Cycles in a bid to create a ‘one size fits all’ solution to bottom bracket needs.

‘We wanted to keep the benefits of a bigger bottom bracket shell,’ says Chris King design manager Jay Sycip.

‘In the case of carbon, this allowed for a stiffer junction, and for metal frames it allowed more area to attach tubing.

It also allows more space for routing cables and hydraulic hoses.

We saw the benefit of the large PF30 shell but really wanted to have threads because it reduced the margin of error when it came to tolerances.’

The larger shell meant that T47 could accommodate both Sram and Shimano crank spindles, unlike the original BSA threaded bottom brackets, making it more versatile.

As such, big brands such as Trek have made the switch to T47 as their preferred standard.

What does the future hold

‘Going forward, it really seems like BB86 is the way for those wanting a press-fit solution.

While BB386EVO should have been well adopted, its similar proportions to T47 made for an easy transition for brands to adopt and promote a threaded BB interface.

In that regard, T47 is leading the way for those after a threaded BB,’ says CeramicSpeed’s Sollenberger.

‘T47 is the biggest disruptor we’ve seen since Cannondale’s BB30, and Cannondale was making its own frames and cranks, so I don’t think we’ll see anything like that again for a while.’

CeramicSpeed isn’t alone in these predictions, either: ‘We’ve had some small frame manufacturers wanting to use BB86 on their new models, but by and large we’re seeing a huge growth in T47,’ says WheelsMFG’s DePaemelaere.

‘It hits all those keys areas, with crank adaptability, the large junction area and the easier tolerances. It kind of has it all.’

It’s unlikely that press-fit, in whatever form, is going anywhere anytime soon.

It has been around too long to simply vanish, and many frame manufacturers will still rely on it for its more economical build process as well as its performance advantages as it’s lighter than T47 while still offering a wide tyre clearance.

It’s clear, however, that T47 has made its mark.

Will someone else throw a new standard into the ring in coming years to shake things up? We think we speak for most when we say we dearly hope not.

Let’s all settle on one or two standards and be done with it.

With Sram looking to be well on its way to standardising derailleur hangers with its UDH design, bicycles could well go back to being the simple machines they once were.

Greatest hits

Favourite BB designs from the people that make them

Dan DePaemelaere, WheelsMFG’s senior sales manager: ‘I would have to say T47 – you can adapt it to any crank spindle you want and it’s got threads, so that’s a win in my books.’

Paul Sollenberger, CeramicSpeed’s head of product management: ‘I love BSA because it’s been around for so long and you know it isn’t going anywhere. I like the classics and BSA is pretty hard to beat.’

Jay Sycip, Chris King’s design manager: ‘On my newer bikes, I chose T47. The junction is bigger and stiffer, and there’s more space for cable routing and hoses.

Innovation never stops

T47 has not long arrived, but some brands are already moving it forward

Not content with conventional T47, US brand Bridge Bike Works has developed an ‘Integrally Threaded Carbon Bottom Bracket’ for its frames.

In this case, the BB threads are moulded directly into the carbon frame and coated with a Cerakote ceramic finish.

Bridge Bike Works claims its bottom bracket is ‘less prone to creaking, ensures the best alignment, holds the bearings securely and is better at keeping road grime out’.

It adopts the same dimensions as the T47 inboard standard but is said to save up to 100g in comparison to the metal sleeves normal T47 necessitates.

It’s a complex and comparatively costly process so it’s unlikely to become an industry standard any time soon, but we applaud the cutting-edge approach.

Elsewhere Felt and Factor have also played around with the T47 concept, mixing and matching the inboard and outboard cups to create T47A, where the driveside cup uses the outboard version and the non-driveside uses the inboard version of the standard.

‘The forces a frame copes with are asymmetrical, so bottom bracket designs should be as well in order to best support frame design,’ says Factor’s head of engineering, Graham Shrive.