In the east of the Utah desert, nestled among ancient sandstone canyons, is Moab – once a small mining town populated by prospectors and cowboys, today a cycling mecca like no place on Earth.

Words James Spender Photography Mike Massaro

There is a type of man to whom time and lifestyle bestows a certain kind of hair.

Matt has this hair, a wonderful snowy bulb offset by the deep tan of a life spent outdoors.

Matt hands my bike up to Dave, who stands on top of the Ford Excursion.

Dave is square-jawed, ex-military and easily 6ft 5in. The Excursion is a true American also, with seats like sofas and wheels like a tractor.

At 4:30am Matt’s sun-visor seems comically redundant, his easy smile in stark contrast to my stinging eyes.

The duo work for Rim Tours, Matt as owner, Dave as guide, and our objective in being up so early and starting this ride not on our bikes but in the truck is to reach the canyons in time to see the sun rise.

For any prospective Moab gravel rider, a self-supported day is feasible, but the going rate in a town where 5,000 locals support five million adventuring tourists annually is that you ride as part of a tour group.

The wilds can be pretty wild.

Blowing a tubeless tyre out here could result in the plot for a moderately successful survival film.

In fact, Aron Ralston, who hacked off his own arm after it got stuck under a boulder (an incident portrayed in the movie 127 Hours), was hiking nearby in Bluejohn Canyon.

Beyond the city limits we are the only visible light save for the returning flashes of nocturnal creatures’ eyes.

The headlights illuminate a continuous face of rock to the right, which could be 10 metres high or a hundred – only the enveloping blackness could say.

‘We call this Wall Street on account of that wall of rock,’ says Matt laconically.

‘Look left and that’s the Colorado River.’ I take his word for it.

With a crunch of tyres and a nodding of the Excursion’s bonnet we leave the road.

Even with the lights on full beam I have no idea how on earth Matt can see where he’s going, let alone where I am.

He and Dave seem nice, but I wonder at how trusting one can be when a couple of blokes say they can drive you out to the desert in the middle of the night to ride bikes.

We come to a stop in a cloud of dust.

Gold in them hills

A half halo of sun peeps over the horizon, tentative at first, then gathering momentum to illuminate the desert in a blaze of orange.

Sandstone mountains are seemingly pulled from the floor by the sun and set aglow like a four-bar fire.

It is breathtaking in the way I imagine early settlers found such sites breathtaking after weeks on the wagon, a vast array of flat-topped mountains – called mesas – flanked by a snaking canyon irrepressibly carved by the Colorado River.

Millennia ago this was all under water, and you can see how.

Bikes unloaded and kit checked, Matt pulls away, leaving us to ride into the mountains.

I’d wager we are the only humans here for miles in every direction, and I’m suddenly overcome with the sheer enormity of the desert and my speck of a place in it.

Dave is less overwhelmed, and cheerily points left then right at two distant promontories: ‘Thelma and Louise drive their car off that one at the end of the film.

That one over there is where the park gets its name.’

Apparently cowboys used these canyons to catch mustangs, which they’d drive down a sliver of land called ‘the neck’ and onto a mesa.

Since the sides of a mesa are so sheer the horses couldn’t escape; all the cowboys had to do was fence off the neck and they gone done got themselves a natural corral.

They would then select the best horses and free the unwanted ‘broomtails’.

Except, one day, whether accidentally or deliberately (it has been mooted the horses competed for food with ranchers’ livestock), the cowboys left the fence closed, leaving the broomtails to perish.

This is an area whose temperatures can rise as high as 46°C, drop as low as -31°C and which gets an average of 10 inches of rain a year.

Dead Horse Point State Park was thus tragically born.

Pedalling on, I marvel at how much Americans always seem to know about where they are.

Dave – who actually moved here from Texas after falling for Matt’s business partner (and his old girlfriend; Moab is a small town), Kirstin – is a historical font.

Moab, Dave explains, is a town built on mining.

First potash, used in fertiliser, which is still drawn out of mines with water from the Colorado River then left to evaporate in vast blue ponds.

Later uranium, which was bought up fervently by the US Government in the 1940s and 1950s for use in nuclear weapons.

‘The uranium boom was like Moab’s Gold Rush,’ says Dave.

‘They got rich. They made a lot of mess and now they’ve had to build a railway to take the leftover radioactive crap 30 miles into the desert so it doesn’t harm the town.’

We arrive at a small wooden sign.

Left turn: White Rim Road.

Right turn: Visitor Center.

Dave assures me the much less fun sounding right turn is what we want.

Sky and stem

This is what brings people here: the hairpins of the Shafer Trail.

At this range the apexes are hidden from view but the diagonals are just visible, slashing away in pink strokes across the sandstone’s ruddy face.

A slowly moving dust cloud indicates a 4×4 is taking on the ascent.

‘This is what we call hood ’n’ sky,’ says Dave.

‘You’re in a Jeep and the road is so steep all you can see is its hood and the sky.’

True to these words, as we round the second hairpin the numbers in the most revered quadrant of my computer screen shoot up to 18%.

I’m glad of every sprocket tooth as I stand on the pedals, simultaneously trying to dig my back wheel into the sand while leaving enough weight over the front wheel to not experience sky ’n’ stem.

This feat has varying degrees of success and wheelspin, and ‘my reward’ comes when the gradient settles into the low teens.

As climbs go, the Shafer Trail is like the bastard child of the Lake District and the Sahara Desert, and further chagrin is added when our near-2,000m of altitude fails to elicit the cool breeze I was hoping for.

Unlike the partly shaded climb, up here there is nowhere to hide from the sun.

There’s a reason Dave has been wearing a long-sleeved top.

We stop for the obligatory achievement-gaze across the canyon, which could be a gargantuan quarry such is the precision with which the cliffs seem excavated.

We are less on a mountaintop than we are gazing into a hole in the floor.

Dave points out a distant white speck, the wreckage of a Jeep that rolled off the cliff when the driver left the handbrake off.

The gravel track ends and joins up with a highway – ‘Island in the Sky Road’ to be exact, so called for the sensation of being up high as the land falls away beneath you.

I check both ways before joining the road, a pointless exercise given the miles of flatness on this prairie-like plateau.

It’s as if we’ve left the coast and are heading into the island’s interior.

That’s good, I think. I’ll write that one down.

Over one shoulder I spy a faraway building – the advertised visitor centre, no less.

Pucker up

The road forks, tarmac turning to washboard gravel then to rock-strewn trail.

We slow to pick better lines across this new surface, and Dave warns the descent could be treacherous.

While officially tagged as Long Canyon Road, the moniker ‘Pucker Pass’ was bestowed on account of its bottom-clenching characteristics.

Only a few weeks ago flash flooding had closed the road and the fallout is still apparent, with deep washes of tyre-swallowing sand interspersed with great lumps of sandstone.

A rock as big as a van has long ago fallen across the track – a collapsed arch, my GCSE Geography senses tell me – no trouble for us to pass under but a stark reminder of powerful elements, and certainly one to watch your roof rack on.

Our pace quickens, in part as I dare not brake too hard for risk of locking up and sliding, the likely outcome of which would be scrambling back up from a dry riverbed a dozen metres below.

But as we descend, said fall becomes ever smaller until we’re actually riding along the canyon’s floor, its cliffs now towering about us in a manner one might see on an ‘I ♥ Moab’ fridge magnet.

After another kilometre of tendon-damaging vibrations plus a suitably puckering rear-wheel slide, the pass peters out into a dusty trailhead car park.

We coast over a set of train tracks parallel to the road – presumably the kind that deals with nuclear waste – and find ourselves on tarmac.

One more spectacle awaits: Jug Handle Arch, a huge hole blasted through the cliffs by rain and wind-blown sand.

It is impressive, albeit it looks as much like a jug handle as any geographic feature ever does when people give it a name.

With the handle in our proverbial rear-view, we take to the road.

It’s the same road we came in on, the huge red walls to the left, the Colorado River to my right.

Only this time I can see both.

Moab-solutely brilliant

Follow our wild tracks through the Moab desert

To download this route, please click here.

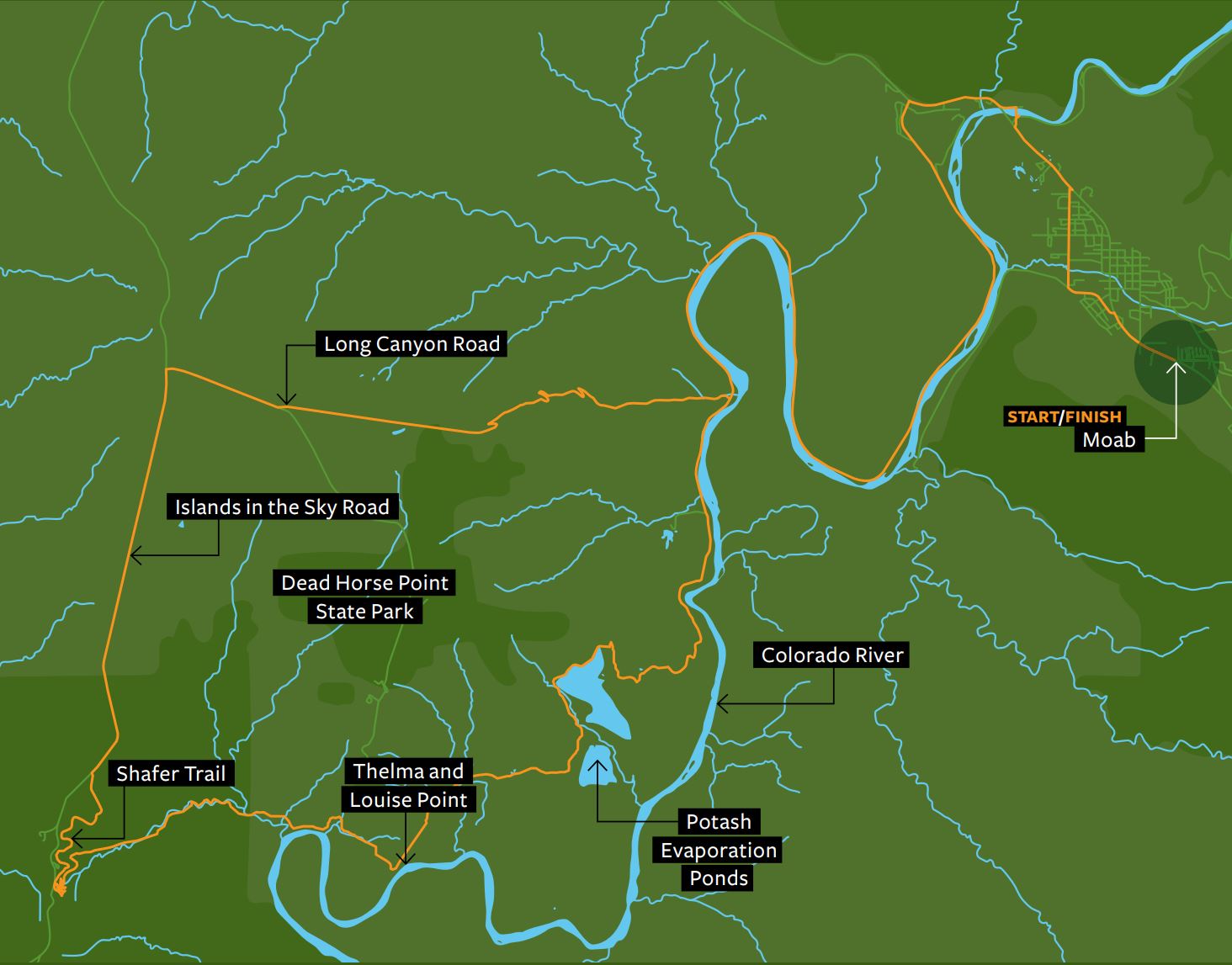

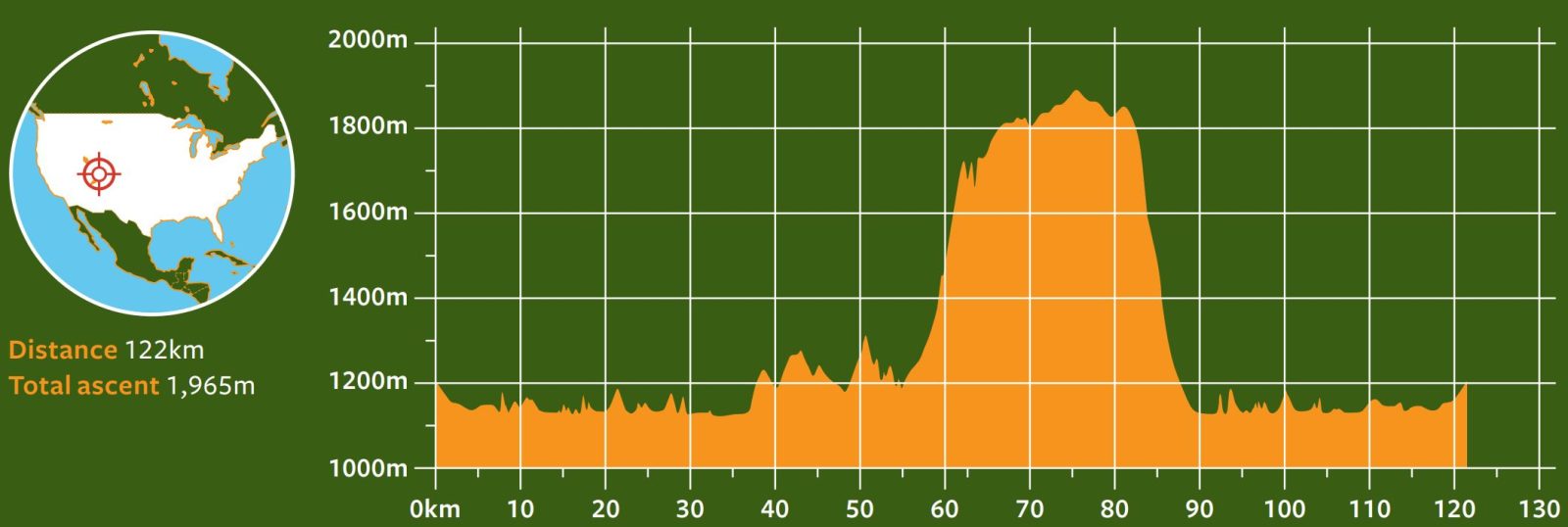

The route starts in Moab, a desert town in the east of Utah.

It heads west along the Colorado River for around 30km on tarmac, before the road turns to gravel, and you make a big loop around Dead Horse Point State Park, taking in Potash Evaporation Ponds, Thelma and Louise Point, and the hairpins of the Shafer Trail along the way.

After 67km you rejoin tarmac on the arrow-straight Island in the Sky Road, before taking the gravelly Long Canyon Road back towards Moab

By the numbers

Statistically speaking

›1,801 Height in metres of Shafer Trail

›18 Max gradient in per cent of Shafer Trail

›5,366 Full-time inhabitants of Moab

›40,000 People who can be in town at any one time in high season

›16 Million tons of uranium by-product to dispose of from Moab mining

›5.12 Litres of sweat disposed of from Cyclist, according to smartwatch

The rider’s ride

Fezzari Shafer, US$3,699 (approx A$5,550), fezzari.com

What better bike to take to Moab than one named after the very climb this ride centres around? In bang for buck alone, this Campagnolo Ekar build is tremendous value.

The carbon frameset hits all the marks, with dropped stays for compliance and huge 50mm tyre clearance; hidden cables up front; 1x or 2x drivetrain compatible and mechanical or electronic groupset ready; mounts for your every luggage whim; and a serviceable set of Fulcrum Rapid Red 500 alloy wheels and house-branded finishing kit.

I was particularly pleased with Ekar’s 10-44t x 40t gearing, and combined with 50mm Schwalbe G-One Bite tyres the Shafer had winch-like capabilities.

However, geometry is the bike’s ace in the hole.

This size medium’s wheelbase is 1,064mm and trail 80mm – numbers that deliver a long, stable bike that’s supremely assured on sketchy descents.

That feeling is bolstered by the huge tyre clearance – 50mm tubeless tyres on 700c wheels feel like they can roll over anything.

The end result is a highly capable bike that punches well above its pricetag.

I only wish I could have taken it home in my suitcase

Slickrock mountain biking

The hallowed trails that made Moab famous

While there’s thousands of kilometres to explore by gravel and road bikes, Moab’s first cycling pilgrims came for its mountain biking, most notably at Slickrock.

Seeming to bubble up from the floor in great bulbous fields, Slickrock appears smooth (and so it was to the early settlers’ metal-shoed horses, hence the name), but closer inspection reveals these petrified sand dunes have a surface like sandpaper, which offers bike tyres startling amounts of grip.

This, plus the weird and enthralling scenery, have made it a mecca for mountain bikers, who can ride the 8km Practice Loop up to the full-blown 19km Slickrock Bike Trail, which takes around four hours for a competent rider to complete.

Cyclist rode Slickrock one evening with bikes hired from Rim Tours, and we can’t recommend it enough – it’s unlike any other place you will ever ride, both visually and technically.

A small fee is payable to enter – $2 for a bike, $5 for a car – and even if you don’t intend to ride, a visit to Slickrock is must for anyone travelling to Moab.

See rimtours.com for more details.

How we did it

Travel

We flew from Sydney to Salt Lake City via LAX with Delta, with return flights costing around $2,200 and taking around 20 hours each way. Utah is big and you’ll want a car, so we hired a vehicle from the very delightful Adam at Enterprise, which cost $1,400 for nine days and was big enough to live in. Driving to Moab takes 3h 45min.

Accommodation

We stayed at the Wingate by Wyndham hotel in Moab (wyndhamhotels.com), with comfortable and affordable rooms (Moab can get pricy in the high season, March-May and September-October). Prices start at around US$95 (approx. $142), and there is a DIY waffle iron at the breakfast buffet. Form an orderly queue.

Thanks

A big thank you to Vicky Brabin of KBC PR & Marketing and Taylor Hartman of Visit Utah (visitutah.com) for their perfect logistical planning. Big thanks also to Kirstin Peterson and Matt Hebberd of Rim Tours (rimtours.com) for their expert guidance, Jordan Washburn of Fezzari Bicycles (fezzari.com) for lending us a bike, and Big Dave Wilson for taking us out riding. Dave also handmakes Nuke Sunrise bike bags, which are both exquisite and very cool (nukesunrise.com).