We’ve featured some of the best climbs in Europe and around the world in our Classic Climbs series, but now it’s time to turn our attention to the home front. This is Mount Hotham Words and

Photography NICK ESSER

Mount Hotham looms large over the Ovens Valley and pretty much all other climbs in the Victorian High Country.

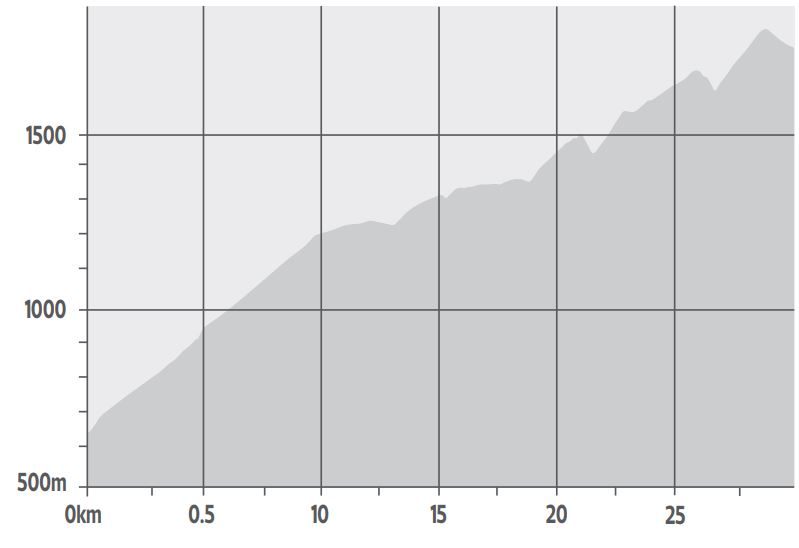

The 30km hors catégorie climb features the largest elevation gain in the region and is the highest sealed road in Australia.

Simply put, this mountain deserves respect.

Don’t be fooled by its average gradient of 4.2%; the climb itself is roughly broken into three parts: a sustained but manageable climb up through tall eucalypts, a delightful false flat and a gruelling series of steep ramps above the treeline punctuated by short reprieves.

Part of Mount Hotham’s lofty reputation is that it features prominently in many events on the Australian cycling calendar – Three Peaks, the Alpine Classic, and the Tour of Bright to name a few.

Cyclists of all sorts – from bearded Audax clichés atop steel-framed tourers to European-based pros on the latest superbikes – battle gravity and occasionally each other up its slopes each summer and autumn.

The back of Falls Creek might be the steepest climb in the area, but Hotham is long, arduous, and unrelenting – an undertaking regardless of bike or ability.

The Meg, the false flat and the Black Hole

Many approach Hotham from the nearby base of Bright, making for a big day and a round trip of about 110km, but the climb itself begins in Harrietville as the road wraps around to the left and the gradient increases.

The lower slopes climb steadily through a series of sweeping switchbacks carved out against a background of old growth forest.

After about 5.5km progress is punctuated by The Meg – the first (of many) steep ramps along the climb.

Named after nearby gold mine Mons Meg – one of the most profitable in the area – here the road rises sharply, spiking at 16% and then holding at 10% for more than 300 metres.

A more reasonable gradient of about 7% follows thereafter and continues until the 11km mark, where the famous false flat begins.

The climb’s second act, an enjoyable 9km false flat, offers spectacular views of the summit as well as the chance to recover somewhat as you take in what lies ahead.

In the meantime, the climb rolls along at an almost unnoticeable gradient, and even heads downhill for a moment.

Those racing, either against others or the clock, will likely shift up into the big ring and go for it, but a more leisurely approach is just as valid as the remaining 11km pack a punch.

At the gap between the Buckland and Ovens Valleys – just after the curiously named Black Hole – the gradient sharpens to about 8% and the third act commences.

A kilometre or so further up the road passes the Dargo-High Plains Road and then shortly afterwards the Wangaratta Ski Club lodge hangs above the road as the ghostly snow gums taper into the alpine.

Act three

Scale is hard to fully appreciate across the High Country.

Stationary ski-lifts line the immediate peaks, but the signs of man’s impact recede as you look out across the Victorian Alps towards Mount Feathertop and then onwards and across the border to Mount Kosciuszko and the Main Range.

The Great Dividing Range might lack the jagged peaks of the European Alps or the elevation of the Andes, but it’s one of the oldest and longest mountain ranges in the world.

And outside of a few old gold mines, a cattle station or two, and a handful of ski resorts, it remains a true and unique wilderness.

Above the trees, the climb now follows the Great Divide, the point from which water flows either north into the Murray Basin, taking a 2,000km journey to meet the sea south of Adelaide, or southward into the Gippsland lakes network and then Bass Strait.

In addition to spectacular views, the ridgeline presents the next significant ramp, CRB Hill – just over a kilometre at 10%.

Renes Lookout eventually arrives after significant effort, offering impressive views north back down the valley and signalling the end of CRB Hill.

The respite, while brief, is welcomed for about 600 metres before the road ramps yet again upwards towards Little Mount Baldy Hill and a short but spectacular descent.

The sting in the tail comes in the form of the pitch up to Diamantina Hut and then past the Razorback, the popular walking track to Mount Feathertop.

While the views are breathtaking, this final ramp is brutal – 1.5km at around 10% coming after nearly 30km of climbing.

The good news is that just around the bend the gradient levels off at The Cross next to Loch Car Park.

The obvious conclusion to the climb follows shortly afterwards at the Hull Bridge.

Named after Mick Hull, a pioneering Victorian skier, in wintertime the bridge delivers skiers down Sun Run and over the Great Alpine Road.

From here it’s a short roll down into Hotham Central, or a kilometre further to Big D, where year-round you’ll find a coffee and bites to eat at The General.

Rain check

Hotham is a fair-weather climb.

If the weather looks doubtful, best give it a miss – a chance of showers in the valley often means snow-flurries on the alpine peaks regardless of the season, and in spring there’s also the chance of a late afternoon thunderstorm.

Until you arrive at the village, there is limited shelter above the treeline and the top of the climb can be exposed to high winds – it’s not the place to weather a passing storm.

When the forecast is less-than-ideal, there are plenty of nearby options throughout the region, the picks of the bunch being either side of Tawonga gap.

In summer and early autumn, Hotham’s elevation means that forecast temperatures throughout the High Country will be 10-15 degrees cooler than Ovens Valley, which can make for delightful conditions.

Just make sure you’re prepared for the sun – it feels much stronger than at sea level. Regardless of the season or the forecast temperature, make sure you bring a jacket or gilet for the descent, which is an absolute blast.

Nick Esser is a cycling writer and photographer who certainly didn’t need a jacket on this occasion

Hotham

The Map

Location Victorian High Country

Start Harrietville

Finish Hotham Heights

Road Great Alpine Road (B500)

The Stats

Summit height 1,832m

Total ascent 1,480m

Distance 29.99km

Average gradient 4.2%

Maximum gradient 18%

Current best Strava times

KoM Brendan Canty 1:07:42

QoM Justine B 1:20:58